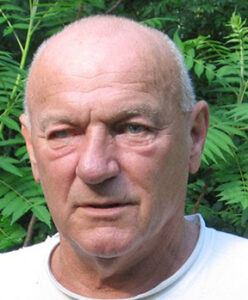

Rev. Carl K. Kabat, OMI, 88, died on August 4, 2022 at Oblate Madonna Residence, San Antonio, Texas.

Fr. Kabat was born to the late Nick and Anna (Skorczewski) Kabat in Scheller, IL, on October 10, 1933. He professed his first vows as a Missionary Oblate of Mary Immaculate in 1957 and was ordained to the priesthood in 1959.

His first ministry assignments were in Minnesota and Illinois, as well as in the Philippines and Brazil. Early on in his priestly ministry, he heard a call to be a prophet against the proliferation and potential use of nuclear weapons. He took seriously Pope St. John XXIII’s statement in his Encyclical “Pacem in Terris” (1963): “Hence justice, right reason, and the recognition of man’s dignity cry out insistently for a cessation to the arms race. The stockpiles of armaments which have been built up in various countries must be reduced all round and simultaneously by the parties concerned. Nuclear weapons must be banned. A general agreement must be reached on a suitable disarmament program, with an effective system of mutual control. In the words of Pope Pius XII: ‘The calamity of a world war, with the economic and social ruin and the moral excesses and dissolution that accompany it, must not on any account be permitted to engulf the human race for a third time.’” (Par. 112) He also took to heart the Constitutions and Rules of the Missionary Oblates: “Action on behalf of justice, peace and the integrity of creation is an integral part of evangelization.” (Rule 9a)

Fr. Carl was willing to put his own freedom on the line to get this message across to governments and individuals. As a result of various actions of civil disobedience, he spent 17 years in federal prisons, seeing those judicial sentences also as a way of being a prophet of peace. He lived for several years at the Karen House Catholic Worker community in St. Louis. The Catholic Worker movement was founded by Servant of God Dorothy Day.

Fr. Kabat was preceded in death by his parents and by his brothers, Paul, Robert and Leonard Kabat. Surviving him is his sister, Mary Ann Radake of Tamaroa, IL as well as nieces and nephews. He is also in the prayerful remembrance of his approximately 3500 fellow Oblates of Mary Immaculate in over 60 countries.

After a Mass of Christian Burial in San Antonio at Oblate Madonna Residence, his cremains will be returned to his native Illinois. There will be Memorial Mass at the National Shrine of Our Lady of the Snows in Belleville at a time to be announced. Burial will be in the Kabat family plot at St. Charles Cemetery, DuBois, IL

In lieu of flowers, memorials may be made to Oblate Madonna Residence, 5722 Blanco Road, San Antonio, Texas 78216.

Kabat did it his way, never fitting any preordained mode. As a priest, he lived simply, attended to the poor, and preached the moral and physical perils of nuclear destruction. In the process he upset many bishops, who banned him from their dioceses. For his part, he seemingly didn’t care. He largely went his own way with the Oblate leadership cutting him lots of slack. Through difficult times, the Oblate mission — “to preach the gospel to the poor” — offered direction on the road ahead.

U.S. Oblate Provincial Fr. Louis Studer is the latest Oblate provincial to have been responsible for Kabat’s priestly ministry. “I’ve come to see him in a much more positive light as I got older,” Studer told NCR. “His dedication has been unparalleled to anyone I’ve ever known. He’s always lived simply and close to the poor.”

“He was just way ahead of his time, trying to draw our attention to the dangers of nuclear war,” said Studer. “You only have to think about the talk of nuclear weapons in Ukraine today to know how on the mark Carl has been.”

Kabat was a passionate and relentless crusader against injustices of all stripes. He viewed militarism as a grave abuse of resources and as antithetical to the Gospels; any church complicity, a betrayal. His life’s work was driven by the belief that humanity is marching blindly toward nuclear Armageddon.

Most Americans don’t know or understand the issues, Kabat had lamented. How are they to know about these issues — about church teachings — if their local bishops and politicians don’t speak about them?

He once handed a reporter a flyer he carried in his pocket. Written on it were words from a Second Vatican Council document, Gaudiem et Spes: “Any act of war aimed indiscriminately at the destruction of entire cities of extensive areas along with their population is a crime against God and man himself. It merits unequivocal and unhesitating condemnation.”

“That’s Vatican II,” Kabat said. “Why don’t they [bishops, cardinals and politicians] teach that? … Because we’re the biggest purveyor of nuclear weapons in the world.”

Kabat spent nearly two decades behind bars as a result of his protests, often involving civil disobedience. Both his parents died while he was in prison. Once released it would often be only months, or even weeks, before he was plotting another act of civil disobedience.

He had a seemingly nonchalant attitude about prison life. He once told a reporter, with a laugh, “I have to get back to jail so I can get back to reading and writing.” He told another: “I’m freer here than on the outside.”

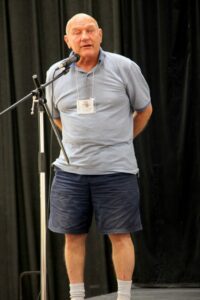

His basic attire — sweats, sneakers, khakis, and shorts — matched his simple, if also eccentric, lifestyle. He was an itinerant protester, not unlike some Old Testament figures. However, he seemed motivated by New Testament teachings. He preached the Beatitudes through his daily actions, often working out of a Catholic Worker house. A Catholic Worker house in St. Louis has been named after him.

“Carl had a really playful and mischievous spirit. Sometimes he would tease, especially if he could discover someone’s soft spot,” said longtime St. Louis-area Catholic Worker Chrissy Kirchhoefer. “He seemed to repel some and bring some much closer to him. He was very thoughtful, inquisitive and loved learning things deeply.”

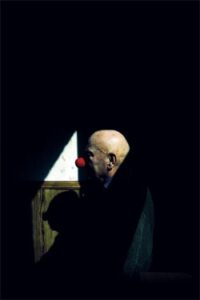

Kabat called himself “a fool for Christ” — a term found in 1 Corinthians 4:10: “We are fools for Christ, but you are so wise in Christ! We are weak, but you are strong! You are honored, we are dishonored!”

He was guided by an inner spirit that cared little what others thought of him. He could be amusing and cultivated levity. To make the point, he often wore a clown costume during his protests, his response to the madness that he saw around him.

“Justice is serious. And nuclear weapons are insane. … My principle is to just do what I can do, and then sing and dance,” he once explained.

His lifestyle took a toll. While in prison he developed complications following a lens implant. Prison staff was dismissive, leading to loss of sight in his right eye.

Kabat’s response was characteristically lighthearted: “I figure I can see with my left eye, better than 20/20,” he told a reporter.

Asked how he would describe Kabat’s personality, Studer said: “He was an ‘in your face’ kind of person.” He said Kabat could be direct and abrupt, “but for those who took the time to listen to him, they found a gentleness at the core.”

Kabat was born on a farm in the small town of Scheller, Illinois, in 1933. He grew up on his parent’s farm, the third of five children: Leonard, Paul, Carl, Bob and MaryAnn.

“Paul was always going to be the priest and Carl was to become a doctor, according to the plan of our parents,” Kabat’s sister, MaryAnn Radake, told NCR. She said he enrolled at the University of Illinois, but returned home at Christmas, miserable. “Medicine was not for him.” Instead, Carl let his brother know he wanted to follow in his footsteps and enter the Oblates, which Paul arranged.

The Oblates had a strong presence in the area. It had a seminary 155 miles away in Belleview. Kabat was eventually ordained in 1959 in Pass Christian, Mississippi, one year after Paul.

The Oblates first sent him to the Philippines. However, it was Kabat’s second assignment, in Brazil, that had the greatest impact on his life, Radake said. There he encountered liberation theology and worked with poor young men, helping to build their self-esteem and Christian consciences. This did not go down well with local authorities who viewed Kabat as a dangerous threat. The Oblates removed him from Brazil for his own safety.

Back in the states, he spent several years translating into English the works of liberation theologian José Comblin. This was a period, after the Second Vatican Council, when priests in both South and North America were waking not just to poverty, but rather to the causes of poverty. It was a radicalizing time in Kabat’s life. He would never see life in the U.S. the same.

Radake recalls that her father, as part of a farm program, was being paid not to grow several crops. This angered and upset Kabat, who saw the program as an attack on the poor of the world. “After Brazil, nothing would ever be the same,” she said. Kabat felt the cost of military weapons was taking food from the poor. He joined Pax Christi USA and Amnesty International.

It was during this period Kabat discovered and found himself being drawn to other Catholics who shared his views. Kabat visited and then joined Jonah House in Baltimore, a faith-based political collective founded by former Josephite priest Philip Berrigan and his wife, Liz McAlister, who’d been a Sacred Heart of Mary sister. (They left their orders to marry).

He joined the Berrigans on multiple protest actions, throwing blood onto the steps of the Pentagon. On Sept. 9, 1980, he was one of eight who broke into the General Electric nuclear weapons manufacturing plant in King of Prussia, Pennsylvania, battering missile nose cones with hammers and sprinkling blood on classified documents.

The group also included Philip Berrigan and his brother, Jesuit Fr. Daniel Berrigan, Dean Hammer, Elmer Maas, Sr. Anne Montgomery, Molly Rush and John Schuchardt; it became known as the “Plowshares Eight.”

That action led to others and soon an anti-nuclear weapons protest movement was growing, called the Plowshares movement. Through four decades, Plowshares protests have been nonviolent and highlighted by symbols, like pouring blood or using hammers. The term “plowshares” comes from Isaiah 2:4: “They will beat swords into plowshares.”

The Plowshares Eight were found guilty, but appeals lasted more than a decade before the group was paroled, in 1990, for up to 23 1/2 months in consideration of time served in prison.

It was during the summer of 1984 I had my first – and most memorable — Kabat encounter. Driving an old clunker, he turned up at my Roeland Park, Kansas, home with the outer shell of a nuclear weapon nose cone hanging out of the trunk. With the help of a friend, he lugged it into the house and placed it on our living room floor. He said he had pulled it from a trash heap outside a nuclear weapons plant. The sight of that metal cone made a lifelong impression on our young children, ages 11 to 6 at the time.

Later that year, in November 1984, Kabat was one of four protesters who cut through a chained fence and broke into the N5 Missile silo 30 miles East of Kansas City, Missouri. Along with Kabat on this protest was his older brother, Paul, Larry Cloud-Morgan (Chief White Feather) and Helen Woodson. They had entered the silo grounds and jackhammered a slab of concrete before being arrested, while sitting in a circle, singing, and holding hands. “To beat the sword into a plowshare, you need a hammer. Well, jackhammer is just a little bigger hammer,” Kabat explained at the time. For that protest, Kabat received an 18-year prison sentence; he served 10.

He returned to Kansas City to engage in a series of civil disobedience actions, in 2011, 2012, 2013 and 2014. During his 2013 protest, Kabat’s then-provincial, Fr. Bill Antone, joined him in trespassing onto the grounds of the Kansas City nuclear weapons plant, saying he did it to protest nuclear weapons, “but mostly to support Kabat.”

“I’m here to be in solidarity with Carl and what he’s done and, in [crossing the line], to show that there is an affirmation and a support and understanding that what he’s done is valid,” Antone said at the time, adding that Kabat had a “heroic persistence” and has been “a real witness to our faith [and is] something that we as oblates can be proud of.”

Kabat often chose July 4 for his protests. He called the holiday “Interdependence Day,” in honor of the interconnectedness of all of nature. During his 2014 action, he took blood from several baby bottles and sprayed it onto a large sign in front of the facility. Then he sat and waited to be arrested.

Kabat had made his life goal known to many: to live a full and joyful life. It seems he has done just that. He told his sister, MaryAnn, that he wants the following words inscribed on his tombstone: “He really lived.” If there’s room, she said, she would try to make it happen.

CARL KABAT, OMI, 1933-2022

So much of Kabat’s fundamental orientation centered around rural Southern Illinois where he and his four siblings were reared on a farm and developed an ethic of hard work where berry picking was permitted on Sundays because it was fun. The main weekend event was the polka dances in the largely Polish community. Carl was so fond of fishing that he kept a seine in his car at all times to cast a net for fish and convince someone to fry up the catch. He took great delight in playing baseball and being an avid life long Cardinals fan. He was an all around natural athlete, wrestling in college and being on a champion basketball team (in prison) well into his sixties.

In contrast, Fr. Luis Valbuena OMI who served as Councilor for Latin America at the Vatican and traveled extensively to the Oblate missions in Latin America in the 1970s shared how the Vatican was following Carl’s activities in Brazil and his subsequent nonviolent actions against militarism in the US. Fr. Valbuena said that there was substantial respect and encouragement within the Vatican and with other oblates for taking the message of the social encyclicals so seriously.

xxx

from St. Louis Magazine

If I Had a Jackhammer

Father Carl Kabat has spent nearly 17 years in jail for civil disobedience. His most common accessory with handcuffs? A clown suit, and a red rubber nose.

A Howard Johnson’s parking lot. The sky’s still dark and full of stars. Eight people stand together: Two priests and a former priest, a nun, a divinity student, a musician, a lawyer, and a housewife. They’re 45 minutes early. Later, the housewife will note she felt perfectly calm, while the lawyer was “deep-breathing like crazy.”

In two cars, they drive to the General Electric plant in King of Prussia, Pa. They need to be there before 7 a.m., before the start of the morning shift. The lot is mostly empty when they arrive. They know exactly in what order they’ll enter Building 9, and what they’ll do once inside; they’ve been role-playing this for more than a year. The Rev. Carl Kabat, in full clerical dress, enters first, followed by tiny, fragile-looking Sister Anne Montgomery, dressed in street clothes. They introduce themselves to 54-year-old Robert Cox, the security guard.

Cox can’t figure out why they’re in the building. Kabat assures him they’re there for peaceful purposes. Cox replies they’re not authorized to be there and they need to leave. They cheerfully refuse. Cox grabs the phone from the wall to call his superior, security Capt. Chester Drobek. Montgomery darts to the cradle and places her fingers on the button, cutting him off.

The other six file swiftly through the lobby, heading toward the doors into the plant. They are Daniel and Philip Berrigan, who made headlines when they set draft records alight in the street with homemade napalm; Elmer Maas, a schoolteacher and musician from New York City; John Schuchardt, a lawyer and former Marine; Molly Rush, a housewife, mother of six, and founder of the Thomas Merton Center in Pittsburgh; and Dean Hammer, who’s just graduated from Yale Divinity School. Montgomery, not wanting to engage in a struggle over the phone, lets go and follows the others.

Cox hollers at them: They’re not authorized to go in there! Kabat wraps Cox in a bear hug until the others are inside.

Cox calls Drobek. Then he hears “this clanging, like metal against metal.” He enters the factory and finds the intruders swinging hammers at the only product made in Building 9, the aluminum nose cones of Mark 12A first-strike nuclear warheads.

The golden nose cones clang like metal drums. The black, carbon-coated ones ring like bells. The noise brings confused employees rushing in. Now Drobek is there, along with the manager of shop operations. Someone calls the police, reporting a riot with hammers and clubs. The protesters put down their hammers and pull plastic baby bottles full of their own blood out of their pockets, sprinkling it over the dented nose cones, the desks, the workbenches, the blueprints and invoices. They hold hands, pray, sing hymns. Kabat remains in the lobby, knelt in prayer, a hammer near his side. It’s all over in minutes.

The trial of the “Plowshares Eight,” as they came to be known—their actions are inspired by Isaiah 2:4, which prophesies that men will beat swords into plowshares and spears into pruning hooks—will not be brief. It drags on for nearly 10 years. Dan Berrigan speaks for the group: “We…wish to challenge the lethal lie spun by GE through its motto, ‘We bring good things to life.’ As manufacturers of the Mark 12A reentry vehicle, GE actually prepares to bring good things to death.”

The Berrigans are held without bail. The other defendants refuse to pay theirs, set at $250,000; that would be an admission of guilt, they feel. Charges include aggravated assault, simple assault, burglary, criminal trespass, criminal conspiracy, disorderly conduct, recklessly endangering another person, harassment, false imprisonment, terroristic threats, and criminal mischief. At the original sentencing, Judge Samuel W. Salus gives the Berrigans and Kabat the stiffest terms—three to 10 years—then adds he’d really like “to send all eight defendants to a leper colony in Puerto Rico to do day-to-day service.” Despite Salus’ determination to set an example, another Plowshares-style action takes place. Then another. And another. And another…

Carl Kabat was born in 1933 in Scheller, a tiny farming town in Southern Illinois. It was a family of boys—Leonard, Paul, Carl, and Bob—until MaryAnn came along 20 years later. Their father farmed a few acres and worked at Southern Illinois Penitentiary. His mother, though deeply religious, was the first in her congregation to defy the mandate that women wear a hat in church. MaryAnn Radake now lives in Tamaroa, Ill., a half-hour from Scheller. Everyone in her family, she says, had a quirky sense of humor.

“We are nut balls, I know,” Kabat cackles. “I’m even more so than most people. Some kid would say, ‘I’d bet you two cents you won’t jump into this pond that’s nothing but mud,’ and I’d do it.”

Radake says that despite the practical jokes, she knows few people who feel things as deeply as her brother does. “He had many alternatives in this life,” she says. That he became a priest was “the hardest thing for people who know him around here—it was like, well, why did he do that? He was going to be a doctor at U. of I. He actually got a speech impediment because of it, because it was not his calling. He couldn’t even talk. He had uncontrollable stuttering.” His brother Paul preceded him into training for the priesthood. “He had mentioned to Paul that maybe he’d like to be a priest. And Paul said, ‘Well—if you want to. Just let me know.’ But then Carl said, ‘But Mom wants me to be a doctor.’ And it was left at that. As he went on about it, he just…it became more than what he mentally could handle, as far as wanting to be a priest and giving it up. It really had nothing to do with the studies, because he’s brilliant. His calling was to be a priest.”

“When I started high school, I thought, ‘I’ll become a doctor and earn enough money and pay what Mom and Dad sacrificed for Paul,’” Kabat says simply. “But then when I was up at the university, I realized that was irrational, a kid’s thinking, eh?”

Kabat was ordained in 1959 by the Oblates of Mary Immaculate in Pass Christian, Miss., one year after Paul. He remembers getting off the bus in New Orleans and seeing two water fountains marked “white” and “colored.” At the time, he says, young priests adhered to “the old way”: Keep your mouth shut. “I should have taken a drink from the black fountain,” he says. Martin Luther King Jr. is one of his heroes—he’s said his only regret is not joining the civil rights marches in Mississippi—along with Gandhi and Franz Jägerstätter, an Austrian peasant beheaded by the Gestapo for refusing to join Hitler’s army. And Jesus, of course. Kabat’s reminded more than one person that Christ was arrested for challenging empire.

“I personally think Jesus had the right method,” Kabat says. “I hate to say it, but Martin Luther King and Gandhi didn’t. Because they went mass-movement. Unfortunately, the followers of Jesus, they went mass-movement, and were co-opted, in my judgment. I think the best thing is people in small groups, doing what they think they should be doing, then letting it go.”

Kabat accepted a mission to the Philippines in 1965. The calling of OMI is to minister to the poor, and they sent Kabat to the right place. “The kids would walk to high school in their bare feet and then put their flip-flops on when they got there,” he says. He returned to Scheller four years later, the day of the moon landing. “Dad and I were watching it on TV,” he remembers. “We walked out to the backyard, and we looked up at the moon, a very clear, bright moon, and Dad said, ‘I just can’t believe it.’”

Kabat ambled into the kitchen, opened the refrigerator. In the Philippines, among his fellow missionaries, only he had a fridge—it ran on kerosene, and the nuns stored their meat in it. Now, back home, the stacks of Tupperware and shrink-wrapped pork chops and jars of condiments stunned him. “That’s a well-stocked fridge!” he exclaimed.

“Mom felt very sheepish about it,” he says. “I didn’t realize that I shouldn’t have said that. When I came back, I realized that I really didn’t fit in… So when there was a possibility of going down to Brazil, I said, ‘Hey, yeah, OK.’”

OMI sent him to Recife, where his parishioners “would go down to this big stream where they would wash clothes,” Kabat recounts in the book Prophets Without Honor. “The stream was filled with their own urine and whatever else. That was also their drinking water.” Kids begged outside his little house every day: “Father, give us some bread.” Always athletic, Kabat became gaunt. He began to throw little church socials for the teenagers, with a battery-powered record player and kerosene lights made from tin cans with wicks. One night, some men in suits appeared and broke up the party. “I told them to get lost,” Kabat says. The next day, OMI flew him out; he’d been charged with inciting revolution.

When he came back to the U.S., in 1973, Kabat felt in his bones that the cost of weapons took food from the poor. He joined Pax Christi USA and Amnesty International. He decided to appeal to the Catholic Church for help, and went to Baltimore for the assembly of the National Conference of Catholic Bishops: “Nobody asked, and nobody invited me, but I thought, ‘Well, maybe I’ll go out and talk to some of these bishops.’” There, he crossed paths with another St. Louis Oblate, the Rev. Larry Rosebaugh, who would soon replace Kabat at the mission in Recife. He sent Kabat to Jonah House in Baltimore, a faith-based political collective founded by former Josephite priest Philip Berrigan and his wife, Liz McAlister, who’d been a nun (they left their orders to marry). Rosebaugh “said, ‘Knock on the door, you can probably sleep on their floor there.’ So I did that,” Kabat recalls. John Schuchardt, who would later take part in the Plowshares Eight action, “took the mattress off his bed. He slept on the box spring… And that was my introduction to that.”

McAlister recalls that Kabat “had come to an understanding in his own life and witness that he needed to be more deeply involved, and in order to do that, he needed others of like mind, and he needed some accountability. And we found that rather fascinating. You don’t often meet people who walk in on you and say, ‘I’m here because I recognize in my own life the need to be accountable to others.’”

Kabat’s first action was an antinuclear picket line in Plains, Ga.—Jimmy Carter’s hometown. Carter had been elected but not sworn in. Jonah House took issue with the new president, Schuchardt says, because “Carter initiated full production of all the first-strike weapons systems that we now have. It was obvious they were not being designed as a deterrent.”

There were nine protesters in Plains, Kabat remembers. “There were three charges: Parading without any permit, blocking traffic, and failure to obey a police officer. Plains had two cops. The closest we could get was about a block away from Carter’s house. And so we unrolled our banner: ‘No more Hiroshimas’ or something like that.” When they’d applied for a parade permit, they’d been told to go to the fourth floor, or the second floor, or come back next week. They finally huddled: “Are we willing to take a bust? And I was one of the nine. So we went back and held our little banner. The cops came…and they booked us.” Then they were tried by “a beggar’s court, a kangaroo court, found guilty on all charges. We were not on the road or the sidewalk, but on the grassy part between. Which is public property, right? And not blocking traffic, unless it was ants going from one side to the other.” But the charge of resisting a police officer? “That’s true,” Kabat says. “Because they said, ‘You can’t do that.’ And we said, well, yes, we could.”

Kabat stayed at Jonah House until 1980, joining the Berrigans on multiple actions, including four where they threw blood on the steps of the Pentagon. In 1984, while the Plowshares Eight case was still working its way through court—the resentencing continued until 1990—Kabat undertook his most radical action to date: Silo Pruning Hooks.

Kabat, his brother Paul, Gaudete Peace and Justice Center founder Helen Woodson, and Larry Cloud-Morgan, a Native American mental-health worker from Minneapolis, breached the fence at Whiteman Air Force Base near Knob Noster, Mo. Using a jackhammer and an air compressor, they battered the concrete cover of a Minuteman II nuclear missile silo, then offered a Eucharist.

“To beat the sword into a plowshare, you need a hammer. Well, jackhammer is just a little bigger hammer,” Kabat roars. “Oh boy. Wow. Helen and I got 18 years, Paul got 10, Larry got eight… The judge said he wanted to set an example.”

Woodson, a mother of 11, served 12 years of that sentence. Three years after being released on parole in 1991, Carl noticed Good Friday and April Fool’s Day would fall on the same day. As luck would have it, he also had a clown suit: his friend Sam Day, publisher of Nukewatch, had rented it for one of Woodson’s kids, then had to buy it after spilling something on it. Kabat borrowed it, packed his bolt cutters, and traveled up to North Dakota. He managed to make some pretty good dents on a silo lid there, and was charged with two Class C felonies, criminal mischief and criminal trespass. Sentenced to five years in prison, he served two and a half.

“Since then,” he says of the clown suit, “I’ve worn it every time I’ve acted against the nuclear business. And I know it’s silly,” he laughs. “Justice is serious. And nuclear weapons are insane, eh? … My principle is to just do what I can do, and then sing and dance.”

For the 20th anniversary of Silo Pruning Hooks, Kabat traveled to missile silo N-8 in Greeley, Colo. He left, but did not use, a jackhammer. He hung banners: “We are fools and clowns for God and humanity’s sake.” And next to the “No Trespassing” sign: “Cessante ratione legis, cessat ipsa lex”—a law that ceases to be rational, ceases to be law.

On an awfully hot August day this year, Carl Kabat, for a change, is not in jail. He’s sitting on the tabletop of the picnic bench outside Kabat House in Old North St. Louis, the Catholic Worker house named after him by friends Tery McNamee and Carolyn Griffeth, who live down the street. He hasn’t been out of jail all that long. Last August, he celebrated his 50th year of ordination at this picnic table with the Catholic Workers. Then, he traveled out to Greeley, Colo., put on his clown suit, clipped open the fence at a Weld County nuclear-missile silo, and waited nearly an hour to be arrested. While he waited, he prayed, fooled around with the silo hatch in an attempt to open it, and hung banners. One read, “We have guided missiles and misguided white men.” Another, pinned to a clown doll that Kabat affixed to the fence, said: “Nuclear weapons are a crime against humanity.” He served four and a half months.

Two Catholic Workers, both named Ben, stop on the street to say hello, addressing Kabat as “Father Carl.” When that title is repeated after they leave, Kabat politely asks not to be addressed that way. “They were just fartin’ around,” he explains, chortling. He continues: “I don’t like to use the term Christian. Christians killed too many people. I’m a follower of Jesus.” He’s fine with Carl, and fine with simple clothes: sweats, sneakers, khakis, shorts. Clerical garments, and clown suits, are for special occasions.

“Tery McNamee and I took Carl out for his last action, in Greeley, and I’ve never seen him so at ease and so calm and so full of peace,” says Chrissy Kirchhoefer, a Catholic Worker friend.

Kirchhoefer stayed for the trial. The jury, though heavily weighted with Air Force personnel, was sympathetic, she says. One chuckled when the “misguided white men” banner was introduced into evidence. Others left the courtroom in tears, not wanting to send a 75-year-old priest to jail. “That really weighed on all of our hearts,” one told the Greeley Tribune. Kabat explained directly to them why he felt the need to do something so extreme: “How many times have you written to your senator, to your congressman? … For some of us, [it’s been] countless times.”

Weld County deputy district attorney David Skarka asked pointedly, “Are you above the law?”

“All wrong law, yes,” Kabat replied. “God’s law is above all these man-made things.”

Kirchhoefer says that when she accompanied Kabat on another action in Denver in 2004, and they went up to the courtroom early, outside the door the marquee read: “USA v. Carl Kabat.”

He joked to her: “So it’s the whole United States against me?”

“But finding that niche and really holding true to it, and pushing and challenging himself and others, I think that really does put him on the fringes,” Kirchhoefer says. “It does a lot of times feel like the U.S. is against Carl Kabat.”

This is part of why Molly Rush, Anne Montgomery, John Schuchardt, and Liz McAlister gathered in Oak Ridge, Tenn., on July 4 to commemorate Plowshares Eight. “You’ll travel great distances at great cost to one’s self to spend time together,” McAlister affirms. “If you feel differently from [the mainstream], you’re going to need to be with people who get it.”

“It was nice down in Tennessee,” Kabat says. “They had a bunch who put on a clown—ah, you might say a clown play, and they paraded. There was a bunch of clowns, and a bunch of kids…”

Rush didn’t know Kabat before Plowshares Eight. “I learned about him in the process,” she says, “and really got to know him and love him. Carl put [the security guard] into a bear hug,” she says, laughing, “and was in no way a threat to this man, although it must have terrified him, because he saw the six of us going past. As you know, Carl was with him, and we’re in there, and the men followed us and came into the test room where we found our nuclear missiles, which we hadn’t planned, or hadn’t known how to find ’em. You know, we sort of went on faith.”

Activists also marked the gathering in Oak Ridge with civil disobedience, marching to the Y-12 National Security Complex, where 13 of them cut through the fence, hung peace cranes, scattered sunflower seeds, and waited for arrest. Kabat was not among them. And he wasn’t with McAlister and Schuchardt in King of Prussia for the second Plowshares Eight reunion in August.

This has been a relatively quiet year for Kabat. On Tuesday nights, there are liturgies at Karen House in St. Louis Place. “I do perform Mass,” he says, “when the opportunity comes up. But I’d rather be with a small group of 10 or 12 rather than 1,200.” He spends time with the young Catholic Workers and the refugees who stay at Kabat House. He reads the paper in the sparsely furnished front room, sits down to a communal meal each night, brings flowers to neighbors when they show up with food donations from Trader Joe’s. He’s hung a sketch someone did of him in prison on the living-room wall, bordered by photos—pictures of baptisms at Karen House, friends on the East Coast, his late brothers. There’s one of the Rev. Larry Rosebaugh, who was murdered in Guatemala last year during a carjacking. Over the mantel, there’s a painting done by a friend of a clown on a cross. Beside it, there’s a ceramic figurine of a clown carrying a suitcase with a luggage label reading “V.I.C. (Very Important Clown).” In that simply furnished front room, Kabat devours every new issue of papers such as Nukewatch and the Nuclear Resister, which he’s reading today. He brings up the fact that there are three new bomb-making plants, including Honeywell’s in Kansas City. “If we’re going to denuclearize, well, why build new factories, you know?”

Protests have already started in Kansas City. Kabat went down “to see people and whatever else, to encourage people to put their arse where their words are,” but “for all kinds of reasons” didn’t join the actions. Other than his clouded right eye, which was damaged during surgery, and his habit of having a cigarette and coffee for breakfast, he’s in good health. Still, Kirchhoefer told the Greeley Tribune that Kabat has been frank with her about how, at his age, he may well end up dying in prison.

If Kabat’s actions were confusing to people 20 years ago—“But what does it all really do?”—that’s amplified when they consider his age. McAlister says you can understand it if you think about his actions as “symbolic yet real… It’s the power of poetry. It’s the power of spirituality. It’s the power of something much deeper than the news reports. It reminds me a bit of the reaction of people who say, ‘You poured blood? I find that disgusting.’ My response is to say, ‘Come and see.’ Because you really don’t get it until you see it. You don’t get it unless you put yourself under that Biblical command and say the world does need this. And by gum, I’m gonna find ways of speaking it, the best ways I know how of speaking it. And I believe that’s what Carl does try to do in his actions, even when he makes those serious moments a little bit less than seemingly serious.”

“Basically, I act for me,” Kabat explains. “You do your own thing; you do it for you. As long as the action has been nonviolent, and public, and resistant to whatever evil… I just do my little thing, and let it go. I’ve done what I can do, and then just kind of enjoy life.”

When he chooses to go may always be a mystery, even to Carl Kabat. Something tickles his spirit when it’s time to pack his stuff into 5-gallon plastic drums, dust off the clown suit, say his goodbyes, and catch another ride. It’s a private thing between Kabat and the force he calls the Holy One, his term for God.

The best portrait of her brother she’s seen, MaryAnn Radake says, is And Carl Laughed, a 2007 play produced at Clayton High School, which traveled to the Edinburgh Festival Fringe. The brilliance of the play, Radake thinks, is that her brother was portrayed as two characters—Carl the Priest, and Carl the Clown. “Carl is that. Carl is serious. But if you stayed that serious about things, you would go mad. The humor has saved him,” she says. “It would be overwhelming to feel the responsibility he feels toward the world.”

The play was co-written by Kelley Ryan, director of theater at Clayton High School, and Nick Otten, the school’s associate theater director. The two clocked hours of tape interviewing Kabat’s Catholic Worker friends, as well as his sister. “In the tapes,” Otten says, “over and over again, someone would say, ‘And then Carl laughed, and told this joke…’” They also wrote to Kabat—who was serving time for breaking into a nuclear-missile silo in North Dakota—who replied with a crisp, 10-point letter.

“I think there is an element of religious ritual to it,” Ryan says of his actions. “The vestments, the sacraments…the collar, he never did wear.”

“He’s like an antinuclear Francis of Assisi, basically,” Otten says.

Ryan and Otten were invited by OMI to talk at Our Lady of the Snows in Belleville. “We did go, and there was a pretty good group of men there,” Ryan says. “There was definitely a dichotomy between the people who appreciated it, and then the others who were angry, because he costs them money…”

“Dichotomy?” Otten interjects. “It was like a bifurcation!”

“They specifically complained,” Ryan says, “there are court costs. They cover that. Meanwhile, the head of the order there gave us a $100 check,” she chuckles, “towards our trip.”

Kabat has seen And Carl Laughed multiple times, once while wearing a clown nose. The first time, he’d been out of jail only a couple of weeks. The kids were days away from leaving for Edinburgh, and performed it for him in the Little Theater at Clayton High. Kabat wept throughout the performance. Then he got up, went down to the stage, and gave every kid a bear hug.

xxx

Fr. Carl Kabat, presente!

On August 4, 2022 God called home Fr. Carl Kabat, OMI, age 88, a renowned Catholic peacemaker and a friend to me and many Catholic Workers, members of Pax Christi USA and the wider faith-based nonviolent movement for peace and justice. He died at the Oblate Madonna House in San Antonio, Texas where he was in hospice care since March.

Born on October 10, 1933 in Scheller, Illinois, the third of five children, Carl grew up on his parents’ farm. He was ordained a priest with the Missionary Oblates of Mary Immaculate in 1959. His ministry including serving in the Philippines and Brazil. In 1976, following his return to the U.S., he became associated with Jonah House, a Christian resistance community in Balitmore, Maryland. During this time, he was arrested for two peace actions at the Pentagon for which he was sentenced to 21 months in prison. Carl had a close affiliation with the Catholic Worker and lived for several years at the Karen House Catholic Worker community in St. Louis.

In 1980 he took part in the Plowshares Eight action, the first plowshares witness involving the symbolic disarmament of nuclear weapons. I can still see and hear Carl leading the singing of “The Lord’s Prayer” at different time during the Plowshares Eight court proceedings. Carl would go on to do seven other plowshares actions. He spent a total of over 17 years in prison for acts of nonviolent witness calling for nuclear abolition. He also was arrested on several occasions for calling for the abolition of the death penalty.

Carl was involved in four plowshares actions addressing the Minuteman II and Minuteman III missile silos. In 1984, his brother Paul, also an Oblate priest, joined him in the Silo Pruning Hooks action at a Minuteman II missile silo controlled by Whiteman Air Force Base in Knob Noster, Missouri.

Considering himself a “fool for Christ,” he dressed as a clown for two of the Missile Silo actions. On April 1, 1994 (Good Friday and April Fool’s Day), while still on parole for the Silo Pruning Hooks action, he entered the Grand Forks Missile Field in North Dakota dressed as a clown. After cutting through a fence surrounding a Minuteman III missile silo (not scheduled to be deactivated under the START I agreement), he proceeded to hammer on a combination dial for the silo as well as the silo lid. He prayed, sang and hung a banner on the silo fence which said “Stop Nuclear Weapons.”

(A play was done about this action — A Clown, a Hammer, a Bomb and God — by playwright Dan Kinch.)

On the morning of June 20, 2006, Carl, along with Mike Walli and Greg Boertje-Obed, dressed as circus clowns and walked on to the Launch Facility E-9 Minuteman III nuclear weapon of mass destruction site in McLean County, North DK, on the Fort Berthold Reservation of the Cheyenne Nation.

In a statement he released explaining his August 6, 2009 plowshares action at a Minuteman Missile silo 30 miles northeast of Greeley in Weld County, CO, he declared:

“The Roman Catholic Church, of which I am a priest, at the close of its Vatican Council II in 1965 condemned nuclear bombs as a crime against humanity and are to be condemned unreservedly. The World Council of Churches has proclaimed that ‘the manufacture, deployment or use of nuclear bombs is a crime against humanity.’ … The nuclear bomb that is in the ground here is more than 20 times more powerful than the atomic bombs we dropped on the Japanese. Each of those bombs killed more than 100,000 people…The Bible says in the words of Isaiah: ‘They shall beat their spears into pruning hooks and their swords into plowshares.’ May the Holy One have mercy on us for not doing so.”

On July 4, 2011 and again on July 4, 2012, Carl entered the property at a nuclear bomb plant under construction in Kansas City, MO. The Kansas City National Security Campus (KCNSC) — formerly known as the Kansas City Plant — is a National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA) facility managed and operated by Honeywell Federal Manufacturing & Technologies that manufactures 85 percent of non-nuclear components that go into U.S. nuclear weapons. Explaining his July 4, 2011 action he declared:

“I, Fr. Carl Kabat, OMI, have been pondering an appropriate way to celebrate the fourth of July, commonly called Independence Day. Today it would be more appropriate to call it Interdependence Day since all of us live on this small planet Earth. To show my patriotism and love for my country and the good of my country, I have decided on a pruning hook action in Kansas City, Missouri. The opinion of the 1995 World Court is that weapons of mass destruction are a crime against humanity. Christian churches have said that it is a sin to build a nuclear weapon. Churches have declared that nuclear weapons are a crime against the Holy One and humanity and are to be condemned unreservedly! Some have further stated that the manufacturing, deployment or use of nuclear weapons must be condemned unreservedly. The Nazis during WWII killed and burned six million of our Jewish sisters and brothers and five million sisters and brothers (who were communists, priests, Gypsies, enemy combatants, homosexuals, people with disabilities, etc). Now four of our Minuteman III’s could, in 30 minutes, go halfway around the world and kill 12 million of our sisters and brothers. We have become very sophisticated and efficient in our killing and burning. We have more nuclear weapons than all the rest of the world combined and at one time could kill everyone on this planet fifteen times over. Eighty-five percent of the parts for nuclear bombs are made by the people of Kansas City. May the Holy One have mercy on us all! By my action I wish to enflesh the reversal of our insane actions and hope that we will start to celebrate an interdependence and rid ourselves of nuclear weapons.”

Compelled by the mandate of Gospel nonviolence and the Vatican II documents condemning nuclear weapons, he implored the USCCB to condemn the possession and threatened use of nuclear weapons as immoral, a stance that would later be adopted by Pope Francis. And a new UN treaty would be enacted making nuclear weapons illegal. In 2017 Pope Francis became the first to declare that the possession of nuclear weapons is immoral. Also in 2017, an overwhelming majority of the world’s nations adopted a landmark global agreement to ban nuclear weapons, known officially as the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW). On January 22, 2021, the TPNW was ratified by 50 nations and entered into force, thereby making nuclear weapons illegal under international law. To date 66 countries have ratified the TPNW, however the U.S. and other eight nuclear armed stated refuse to do so.

Tragically, despite enduring long imprisonment for his steadfast Gospel witness, Carl was not supported by the U.S. Catholic hierarchy. His relationship with his own order was lacking in support and difficult. However, later in his peace ministry this relationship changed. During Carl’s 2013 protest, his then-provincial, Fr. Bill Antone, joined him in a witness at the Kansas City nuclear weapons plant, saying he did it to protest nuclear weapons, “but mostly to support Kabat.” “I’m here to be in solidarity with Carl and what he’s done and, in [crossing the line], to show that there is an affirmation and a support and understanding that what he’s done is valid,” Antone said at the time, adding that Kabat had a “heroic persistence” and has been “a real witness to our faith [and is] something that we as oblates can be proud of.”

I first met Carl in the late 1970s and for over four decades he was a great inspiration. In between prison stints, Colleen McCarthy and I were blessed to have him present at our wedding. He was also an athlete who enjoyed playing basketball. It was always great fun to play with him, even if he always invoked the “Kabat Rules.” He was also an avid St. Louis Cardinals baseball fan.

During the last four months I was able to have several “virtual” visits with Carl through WhatsApp, arranged by two longtime friends, Chrissy Kirchhoefer and Cassandra Dixon, who were accompanying him during his time in hospice. During my time with him his eyes were mostly closed, he was resting comfortably and he didn’t speak. I did make a point to convey to Carl, via Chrissy and Cassandra, the love and prayers from many of his friends and co-conspirators. Chrissy and Cassandra said he could hear what I was saying and was able to open his eyes and smile at me at different times.

Chrissy, Cassandra, and Carl’s sister Mary Ann were with Carl earlier this week singing, holding his hand and lovingly tending to him. When they were with him on Wednesday (the day before he died), before leaving he was attentive the whole time and even seemed to sing of sorts while his head was being massaged. They conveyed to Carl everyone who was sending their love and prayers.

Carl’s spirit was indomitable and his steadfast faith in following the nonviolent Jesus was exemplary. During this August 6-9 time marking the 77th anniversary of the criminal U.S. nuclear bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, let us recommit ourselves to working for the abolition of nuclear weapons and a disarmed world and making God’s reign of justice, love and peace a reality.

Deo Gratias for the life, friendship and courageous Gospel witness of Carl Kabat who is now among the holy cloud of witnesses advocating for us!

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DLATpydLAcc

Carl entered the seminary as a first year collegian. The understanding within the family was that his older brother, Paul, would become a priest, and Carl would become a doctor. One semester at the University of Illinois was enough to convince Carl otherwise: He accompanied Paul to St. Henry’s after Christmas, then followed him to the Oblate novitiate at Godfrey and on to ordination as a Missionary Oblate of Mary Immaculate.

He took the stand in his own defense. The prosecutor asked him, “Are you above the law?”

Carl’s actions spoke louder than his (or anyone else’s) words, but let me close with these inspiring words of his:

xxx

from Catholic Review

WASHINGTON (CNS) — Oblate Father Carl Kabat, a former Baltimore resident who routinely described himself as a “fool for Christ” for his many faith witnesses challenging U.S. nuclear weapons policy, died Aug. 4 at his religious order’s Madonna Residence in San Antonio. He was 88.

His witnesses and acts of civil disobedience spanned more than four decades and included what was the first plowshares action in 1980 to symbolically dismantle nuclear warheads.

A funeral Mass was celebrated Aug. 6 in the chapel at the residence.

Father Kabat devoted most of his priesthood to protesting what he considered to be misguided government and military preparations for nuclear war. In addition to the Plowshares Eight action, he joined seven other plowshares and civil disobedience symbolic disarmament protests, for which he served more than 17 years in prison.

The 42-year-old plowshares movement takes its name from the Book of Isaiah’s call to beat swords into plowshares and for nations to end war.

Father Kabat told Catholic News Service in 2009 that being jailed did not bother him. He spoke to CNS as he awaited sentencing for cutting a hole in a fence surrounding a missile silo in rural Colorado and hanging banners with joyful message of peace. He was turning 76 at the time.

The priest regularly reminded people that Jesus was arrested for challenging the Roman empire.

During one of his imprisonments, Father Kabat became blind in his right eye when complications developed after cataract surgery. Even so, he remained an avid reader.

Father Kabat was born Oct. 10, 1933, to the late Nick and Anna Kabat on a farm in Scheller, Ill., the third of five children.

He decided to become a priest after leaving college, following the path of his older brother Paul, who also had joined the Oblates. He professed his first vows as a Missionary Oblate of Mary Immaculate in 1957 and was ordained a priest in 1959. Early in his priesthood he was assigned to ministries in Minnesota and Illinois and then was sent to Philippines and Brazil.

Reading St. John XXIII’s 1963 encyclical “Pacem in Terris” (“Peace on Earth”) influenced him to begin peacefully protesting the possession and potential use of nuclear weapons. Father Kabat joined his first nonviolent protest in Plains, Ga., the home of President Jimmy Carter, who supported production of first-strike nuclear weapons systems.

The priest later moved to Jonah House, a collective in Baltimore, which worked for peace and ministered alongside poor residents in their neighborhood. It has been the home of several plowshares participants over the years. It’s where he met attorney John Schuchardt, who also was one of the Plowshares Eight.

Schuchardt recalled Father Kabat as a person who was determined to call out what he considered the misguided military and government policy regarding the potential use of nuclear weapons in war.

“Looking at Carl’s 17 years in prison, here was someone whose greatest gift was hope,” Schuchardt, 83, told CNS Aug. 8. “What do you manifest when you are imprisoned again and again and again? You act for truth for the eventuality of humanity waking up. You wake up every day with the gift of hope.”

Schuchardt, director of House of Peace in Ipswich, Massachusetts, said the Oblate’s life “was a ministry.”

“He was a witness to the risen Christ. He had experienced the risen Christ. He was the resurrection,” Schuchardt said.

Art Laffin, a member of the Dorothy Day Catholic Worker in Washington, recalled Father Kabat in a reflection posted on the Pax Christi USA website, saying his priest friend considered himself a “fool for Christ.”

The reference comes from the First Letter to the Corinthians, which says: “We are fools for Christ, but you are so wise in Christ! We are weak, but you are strong! You are honored, we are dishonored!”

Laffin said the priest at times would dress in a clown suit to demonstrate the absurdity of U.S. nuclear weapons policy. At his protest actions, he often would display peace banners on fencing surrounding the target of his angst, Laffin said.

Schuchardt said Father Kabat would often break into song during his trials, singing spiritual hymns that highlighted calls for peace and belief in the Resurrection.

Father Kabat continued to protest nuclear weapons until 2014. [note from Nuclear Resister: Carl’s last arrest was at the Kansas City nuclear weapons plant on July 4, 2019.] He lived at a Catholic Worker house in St. Louis until moving to the Oblate residence in his later years.

Survivors include a sister, Mary Ann Radake of Tamaroa, Ill., nieces and nephews. Brothers Paul, Robert and Leonard preceded Father Kabat in death.

xxx

by Frank Cordaro, in Via Pacis

Fr. Carl was 88 years young when he died. I say ‘young’ because the spirit I got from talking and listening to Carl over the years, about his witness against nuclear weapons and years of prison time, was always childlike ((Matthew 18:3). For Fr. Carl,when it came to nuclear weapons, there was nothing complicated or dogmatic about what was needed. For Fr. Carl, nuclear weapons were evil. They had no right to exist. And because Church and State were not taking responsibility for their disarmament, he and everyone else must do everything they can to nonviolently disarm them at our own personal risk.

Fr. Carl has the distinction of serving more prison time than any other nonviolent U.S. nuclear resister – a total of 17 years!

I first learned about Fr. Carl when his name was on the original 1980 Plowshares 8 Witness list of actors. Father Dan and Phil Berrigan were the best known of course. And I knew something of everyone else, except for who Fr. Carl Kabat was.

That all changed in November 1984, with the Pruning Hooks Plowshares witness. Fr. Carl was one of four protesters who cut through a chained fence and broke into the N5 missile silo 30 miles east of Kansas City, Missouri. Along with Carl was his older brother, Paul, Larry Cloud-Morgan (Chief White Feather), and Helen Woodson. They had entered the silo grounds and jackhammered a slab of concrete before being arrested.

The use of a jackhammer got my attention, and the Federal Government’s attention as well. When asked about this at the time Fr. Carl said “To beat the sword into a plowshare, you need a hammer. Well, a jackhammer is just a little bigger hammer.” For that protest, Fr. Carl received an 18-year prison sentence; he served 10. Carl would go on to do five other plowshares actions.

I took to writing Fr. Carl while he was locked up after this Pruning Hooks Plowshares witness. We put him on our via pacis mailing list. There must be a small pile of postcard notes from Fr. Carl in the DMCW Archive boxes in the CW Archives at Marquette University. And over the years, when he was not locked up, Carl started to attend our Midwest CW gatherings at Sugar Creek and the yearly Faith and Resistance Retreats. For a number of those years until his retirement, Fr. Carl lived with the St. Louis Catholic Worker. He was our preferred Eucharist presider at all our CW gatherings.

Though childlike, he wasn’t perfect. Sometimes Carl’s hard headedness, stubborn ‘going my way’ attitude did not serve him well. Fr. Carl was at his best for us Midwest Catholic Workers when he celebrated Mass for us. It was easy to pray with Fr. Carl. Great scripture reflections, shared bread and wine duties, personal and humble. And there is that time we were at a Fr. Carl Mass and he managed to skip the whole Cannon. We all took it in stride and knew the bread and wine was Jesus.

A giant “Thank-you” to St. Louis Catholic Worker Chrissy Kirchhoefer for being one of Carl’s primary support persons, being there for Carl when he needed help. Chrissy was with Carl when he died.

Here is childlike Fr. Carl in his own words explaining to a Federal Judge why he was part of a August 6, 2009 plowshares action at a Minuteman Missile silo in Colorado: “The Roman Catholic Church, of which I am a priest, at the close of its Vatican Council II in 1965 condemned nuclear bombs as a crime against humanity and are to be condemned unreservedly. The World Council of Churches has proclaimed that ‘the manufacture, deployment or use of nuclear bombs is a crime against humanity.’ … The nuclear bomb that is in the ground here is more than 20 times more powerful than the atomic bombs we dropped on the Japanese. Each of those bombs killed more than 100,000 people…The Bible says in the words of Isaiah: ‘They shall beat their spears into pruning hooks and their swords into plowshares.’ May the Holy One have mercy on us for not doing so.“

(A play was done about this action — A Clown, a Hammer, a Bomb and God by playwright Dan Kinch.)

xxx

Fr. Carl Kabat and Chrissy Kirchhoefer in 2019 outside a former nuclear missile silo near Mayview, MO, where Kabat and three others participated in a 1984 protest. (photo by Byron Clemens)

from the Washington Post