Daniel Berrigan, Uncle, Brother, Friend

PRESENTE

A statement from the Family of Father Dan Berrigan, SJ

This afternoon around 2:30, a great soul left this earth. Close family missed the “time of death” by half an hour, but Dan was not alone, held and prayed out of this plane of existence by his friends. We – Liz McAlister, Kate, Jerry and Frida Berrigan, Carla and Marc Berrigan-Pittarelli—were blessed to be among friends—Patrick Walsh, Joe Cosgrove, Father Joe Towle and Maureen McCafferty—able to surround Daniel Berrigan’s body for the afternoon into the evening.

We were able to be with our memories of our Uncle, Friend and Brother in Law—birthdays and baptisms, weddings and wakes, funerals and Christmas dinners, long meals and longer walks, arrests and marches and court appearances.

It was a sacrament to be with Dan and feel his spirit move out of his body and into each of us and into the world. We see our fathers in him—Jerry Berrigan who died in July 2015 and Phil Berrigan who died in December 2002. We see our children in him—we think that little Madeline Vida Berrigan Sheehan-Gaumer (born February 2014) is his pre-incarnation with her dark skin, bright eyes and big ears.

We see the future in him – his commitment to making the world a little more human, a little more truthful.

We are bereft. We are so sad. We are aching and wrung out. Our bodies are tired as Dan’s was—after a hip fracture, repeated infections, prolonged frailty. And we are so grateful: for the excellent and conscientious care Dan received at Murray Weigel, for his long life and considerable gifts, for his grace in each of our lives, for his courage and witness and prodigious vocabulary. Dan taught us that every person is a miracle, every person has a story, every person is worthy of respect.

And we are so aware of all he did and all he was and all he created in almost 95 years of life lived with enthusiasm, commitment, seriousness, and almost holy humor.

We talked this afternoon of Dan Berrigan’s uncanny sense of ceremony and ritual, his deep appreciation of the feminine, and his ability to be in the right place at the right time. He was not strategic, he was not opportunistic, but he understood solidarity—the power of showing up for people and struggles and communities. We reflect back on his long life and we are in awe of the depth and breadth of his commitment to peace and justice—from the Palestinians’ struggle for land and recognition and justice; to the gay community’s fight for health care, equal rights and humanity; to the fractured and polluted earth that is crying out for nuclear disarmament; to a deep commitment to the imprisoned, the poor, the homeless, the ill and infirm.

We are aware that no one person can pick up this heavy burden, but that there is enough work for each and every one of us. We can all move forward Dan Berrigan’s work for humanity. Dan told an interviewer: “Peacemaking is tough, unfinished, blood-ridden. Everything is worse now than when I started, but I’m at peace. We walk our hope and that’s the only way of keeping it going. We’ve got faith, we’ve got one another, we’ve got religious discipline…” We do have it, all of it, thanks to Dan.

Dan was at peace. He was ready to relinquish his body. His spirit is free, it is alive in the world and it is waiting for you.

xxx

Click here for Democracy Now! show about Dan Berrigan, 5/2/16

How Friends & Family Remember Daniel Berrigan, gathered by Eric Stoner on Waging Nonviolence – click here to read

Dan Berrigan’s funeral mass here

What the Obituaries Missed About my Uncle, Dan Berrigan, by Frida Berrigan – click to read here

The Death Stops Here: The Death and Resurrection of Daniel Berrigan, by Jeremy Varon – click to read here

Bearing the Cross, by Chris Hedges – click to read here

Dan Berrigan: We Haven’t Lost, Because We Haven’t Given Up, by John LaForge – click to read here

Daniel Berrigan Through the Eyes of a 1960s Ithaca Mom, by Ellen Murphy – click to read here

xxx

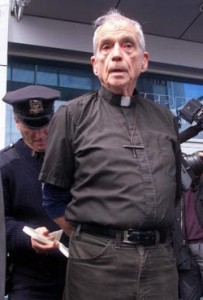

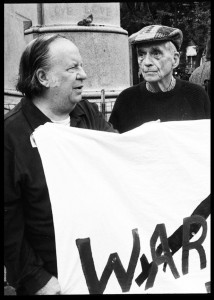

photo by Ananda Strazzini: Dan’s last arrest, Good Friday, at the “USS Intrepid” Museum, 2 April 2011

from National Catholic Reporter

by Patrick O’Neill

Daniel Berrigan, priest, prisoner, anti-war crusader, dies

After a year of studying and ministering in France, where he met some worker-priests who gave him, he wrote, “a practical vision of the church as she should be,” he was assigned to teach theology and French at the Jesuits’ Brooklyn Preparatory School.

In 1957, Berrigan was appointed professor of New Testament studies at Le Moyne College in Syracuse, and he won the Lamont Poetry Prize from the Academy of American Poets for his book of poems, Time Without Number. He would go on to publish more than 50 books of poetry, essays, journals and scripture commentaries.

However, it was his anti-war work for which Berrigan gained his most notoriety, spending approximately two years of his life in jail and prison.

He joined other prominent religious figures like Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel, the Rev. Richard John Neuhaus, then a Lutheran pastor, and the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. to found Clergy and Laity Against the War in Vietnam. In February 1968, he traveled with historian Howard Zinn to North Vietnam and returned with three American prisoners of war who were released as a goodwill gesture.

Rabbi Michael Lerner, met Berrigan when Lerner was the chair of Students for a Democratic Society at the University of California Berkeley. Lerner recalled that meeting in a statement issued May 1. “He told me,” Lerner wrote, “that he had been inspired by the civil disobedience and militant demonstrations that were sweeping the country in 1966-68 … Over the course of the ensuing 48 years I was inspired by his activism.”

“Heschel told me how very important Dan was for him — particularly in the dark days after [President Richard] Nixon had been elected and escalated the bombings in Vietnam, Cambodia and Laos.

“Those of us who were activists were particularly heartened by [Berrigan’s] willingness to publicly challenge the chicken-heartedness and moral obtuseness of religious leaders in the Catholic, Protestant and Jewish world who privately understood that the Vietnam war was immoral but who would not publicly condemn it and instead condemned the nonviolent activism of the anti-war movement.”

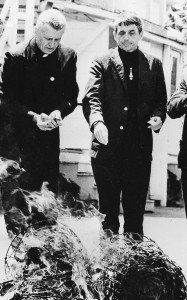

Berrigan will forever be mentioned in the same breath as his late brother, Philip, who died of cancer Dec. 6, 2002. The brothers were constant companions in crime, arrested together at the Select Services System office in Catonsville, Md., May 17, 1968, for using homemade napalm to burn draft files. A dozen years later, Sept. 8, 1980, while spearheading the faith-based opposition to the nuclear arms race, the Berrigan brothers and six others, brazenly forced their way into a General Electric armaments factory in King of Prussia, Pa., and pounded on two Mark 12A nuclear missile nose cones with simple carpenters hammers to, as they described it, disarm the weapons. Inspired by a passage from the Isaiah, they symbolically sought to turn swords into plowshares.

Berrigan will forever be mentioned in the same breath as his late brother, Philip, who died of cancer Dec. 6, 2002. The brothers were constant companions in crime, arrested together at the Select Services System office in Catonsville, Md., May 17, 1968, for using homemade napalm to burn draft files. A dozen years later, Sept. 8, 1980, while spearheading the faith-based opposition to the nuclear arms race, the Berrigan brothers and six others, brazenly forced their way into a General Electric armaments factory in King of Prussia, Pa., and pounded on two Mark 12A nuclear missile nose cones with simple carpenters hammers to, as they described it, disarm the weapons. Inspired by a passage from the Isaiah, they symbolically sought to turn swords into plowshares.

Scores of activists, mostly Catholics, followed the Berrigans’ lead, participating in similar draft board raids and Plowshares actions.

Addressing many issues, during a life of activism

Former U.S. Attorney General, Ramsey Clark, 88, who maintained a close association with the Berrigans and sometimes represented Philip in court, said he was fortunate to have known Dan for many years.

“I’ve not known a more wonderful human being, kind and pious and good,” Clark said, “and he lived a long and peaceful life from what I saw, always instructive. He was an inspiration to those who knew him and always optimistic, so we need more Dan Berrigans, and we’ll miss him greatly.”

Clark said Dan Berrigan was “a very sensitive person” and that his anti-war protests were hard on him. “I remember his testimony at one of the trials, where he said — as frightening as it was — he could not not do it. He was an extraordinary gentle person who did not like conflict or confrontation, but yet found a need to stand up to war.

“He and Phil were loving brothers, but so different in many ways, but they had such enormous love and respect for each other. It inspired everybody who knew them both.”

Frida Berrigan, who frequently visited her uncle, bringing along her two young children, said her father and uncle had a great bond. “Dad would talk about Dan as his best friend,” Frida said. “They trusted each other completely, trusted each other with their lives.”

The Catonsville caper led to a three-year federal prison sentence, which was preceded with Dan Berrigan going underground, all the while playing a game of cat and mouse with the FBI. With the help of anti-war friends, Berrigan stayed on the lam for four months, giving interviews and even speaking publicly against the Vietnam War.

“I knew I would be apprehended eventually, but I wanted to draw attention for as long as possible to the Vietnam War, and to Nixon’s ordering military action in Cambodia,” Berrigan told America magazine in a 2009 interview.

Berrigan’s life of resistance was also influenced by his personal friendships with Catholic Worker founder, Dorothy Day, who Berrigan met in the 1940s while teaching at Jesuit schools in New York City, and with Trappist monk Thomas Merton, who Berrigan met in the 1960s.

As Berrigan’s anti-war activities expanded and his visibility and that of his brother, increased, Jesuit superiors ordered Berrigan to be transferred to Latin America. Berrigan left, but his so-called forced exile brought heat on the Jesuits and Berrigan returned to the United States after just four months.

Throughout his activist life, Berrigan addressed issues as they came his way. He supported and visited young IRA prisoners on hunger strikes in the Northern Ireland. He defended the reputation of an American Quaker, Norman Morrison, who shocked the nation when on Nov. 2, 1965, he immolated himself on the grounds of the Pentagon in a protest against the Vietnam War. Berrigan also protested capital punishment and U.S. military intervention.

Berrigan received criticism from the political left for his pro-life views. He was a longtime endorser of the “consistent life ethic,” and he served on the advisory board of Consistent Life, an organization that describes itself as “committed to the protection of life, which is threatened in today’s world by war, abortion, poverty, racism, capital punishment and euthanasia.”

“I have always made it clear,” Berrigan said in the America interview, “that I am against everything from war to abortion to euthanasia. I have avoided being a single-issue person.”

Berrigan was arrested in 1992 protesting outside a Planned Parenthood in Rochester, N.Y.

In the 1980s, he began ministering to patients with AIDS in New York City, work he stayed with through the 1990s. Berrigan was an advisor to the film 1986 “The Mission,” about 18th century Spanish Jesuits in South America, and had a cameo appearance.

Berrigan also showed a sense of humor, when during a “60 Minutes” segment that aired in the 1980s, titled “The Brothers Berrigan,” he commented that getting arrested, handcuffed and placed in the paddy wagon was like a receiving a “spiritual enema — everything’s all clear at that point.”

Berrigan: ‘Make your story fit into the story of Jesus’

Reflecting on her brother-in-law’s contributions to her family’s life, McAlister told a story of a ritual Dan spearheaded at family gatherings.

“We’d have an evening together and toward the end of the evening you could sense it coming; [Dan] would throw out a question, and say a little bit about it himself, then ask each in the circle to address that question.

“And of one that I remember vividly is, ‘What’s giving you hope these days?’ And he wanted us to elaborate on that in terms of all of the things that appeared so hopeless and then just invite and encourage people in that circle to address that. And what came out was absolutely stunning.

“We began to look on that as the highlight of visits from Dan in our household, because it made such an impact on all of us and it led to such a depth of sharing from all of us.”

A few years ago, with Berrigan already in declining health, Jesuit Fr. Luke Hansen agreed to take Berrigan to Baltimore to spend Christmas with McAlister and her family at Jonah House, a resistance community founded by McAlister and her husband.

“Sitting in the living room I encouraged Dan to move in that direction, but he didn’t feel up to it, so instead I raised something and it was like continuing and like opening again a tradition, a gift that Dan had given to us as a circle of family and friends. And it was so powerful.

“Luke Hansen was profoundly moved by this evening. He said, ‘I go home for Christmas and we watch football. I’ve never been part of circle where this kind of a sharing is done in a family.’ And I said, ‘This is Dan’s gift. This is what he has brought us to all of my life with him, and we’re just trying to continue this thing that’s one aspect of life with him that has been particularly precious.'”

McAlister continued: “You know you can talk about all of the public witness [that Berrigan did], but that public witness comes out of that kind of soul-searching in a circle of community and family, that strengthens people and clarifies things for people to be able to get up and get out and be public. And when I think of Dan, and when I think of all the gifts he has given us, this is perhaps the most precious to me.”

John Dear, a former Jesuit who lived with Berrigan and edited his writings, called Berrigan, “My greatest friend and teacher, one of the greatest peacemakers, a great saint and a prophet.”

Dear said that Berrigan “changed the history of the Catholic church, not just in the United States, but in the whole world. He influenced millions, perhaps hundreds of millions of people. I consider Dan to be in the same league as Gandhi, Martin Luther King, Dorothy Day and his brother Phil.”

Dear said he once asked Berrigan, ” ‘What’s the point of all this, Dan?’ and he said to me, ‘All you have to do is to make your story fit into the story of Jesus.’ And I thought that was the most profound answer; I still do. He could have said you do the work to end all war, but he told me to make sure I fit my life story into Jesus’s story. Now I think that’s what he did.”

In a reflection about Berrigan, pacifist David McReynolds, a longtime staff person at the War Resister’s League in New York City, wrote April 30: “There will be great sadness, but also joy at a life so well and truly lived, as an act of poetry in a world so bloody and violent.”

Frida remembers that for her and her siblings, who did not have grandparents, Berrigan filled a void. Dan was “a kind uncle who is just so different,” Frida said. “He lived in New York City. It was so great to continue to go to that same space where Dan lived on 98th Street, continuously seeing him and visiting him. Just being in his space was so meaningful.

“He would write on the wall, notes, sayings, poetry with magic marker. It was unlike any other place we would go. He aged, but he never did really change. Life is always in flux, things continually change, but he was a constant.”

As a child, Frida said she remembers walking down the street with Berrigan on New York’s Upper Westside — “jaunty happy walks. He really observed things and people, interacted with a lot of people. Here is a guy who really enjoyed life, and enjoyed people and was celebrating God’s love.

“To have his full attention as a kid was a real gift. I had an audience with him. He would give us his full attention. I got his full attention. It was just such a pleasurable experience for all of us. He appreciated it.”

On April 29 as she was on her way to her family weekend, Frida stopped to see her uncle for what was the last time. Reflecting on that visit shortly afterward, Frida wrote on her last previous visit, Berrigan “laughed at the kids’ antics and was almost jolly by comparison.”

April 29 was different.

“I went into his room, happy — for once — that I did not have small energetic children in tow. He did not really register me being there at all,” Frida wrote. “I tried to talk the whole time: reading from To Dwell in Peace, [Berrigan’s autobiography] which was almost impudent in its Dan-ness, full of turns of phrase and unpronounceable words. …

“Sian, his aide, came in to check on him and try to gently rouse him, but he would not wake. I showed her and Sofina, the nurse, pictures of Dan at [ages] 7 and 10. … It was sweet but sad. Hard to watch his labored breathing — hard to be there, harder to leave.”

Frida planned to visit her uncle again on Sunday, May 1, after the family reunion. He died Saturday.

[Patrick O’Neill is a longtime NCR contributor.]

xxx

from Common Dreams

from Common Dreams

The Life and Death of Daniel Berrigan

by Rev. John Dear

Rev. Daniel Berrigan, the renown anti-war activist, award-winning poet, author and Jesuit priest, who inspired religious opposition to the Vietnam war and later the U.S. nuclear weapons industry, died at age 94, just a week shy of his 95th birthday.

He died of natural causes at the Jesuit infirmary at Murray-Weigel Hall in the Bronx. I had visited him just last week. He has long been in declining health.

Dan Berrigan published over fifty books of poetry, essays, journals and scripture commentaries, as well as an award winning play, “The Trial of the Catonsville Nine,” in his remarkable life, but he was most known for burning draft files with homemade napalm along with his brother Philip and eight others on May 17, 1968, in Catonsville, Maryland, igniting widespread national protest against the Vietnam war, including increased opposition from religious communities. He was the first U.S. priest ever arrested in protest of war, at the national mobilization against the Vietnam war at the Pentagon in October, 1967. He was arrested hundreds of times since then in protests against war and nuclear weapons, spent two years of his life in prison, and was repeatedly nominated for the Nobel peace prize.

***

Daniel Berrigan was born on May 9, 1921 in Virginia , Minnesota , the fifth of six boys to Thomas and Frieda Berrigan. His family subsequently moved to Syracuse , New York, where the boys grew up attending Catholic grade schools. After high school, Berrigan applied to the Society of Jesus, the Catholic religious order known as “The Jesuits.” He entered the Jesuit novitiate at St. Andrew-on-the-Hudson, near Poughkeepsie , New York in August, 1939.

With his classmates, he made the Spiritual Exercises of St. Ignatius, a thirty-day silent retreat; spent two years studying philosophy; went on to teach at St. Peter’s Prep in Jersey City, New Jersey (from 1946-1949); and eventually, to study at Weston School of Theology in Cambridge, Massachusetts (from 1949-1953).

Berrigan was ordained a priest on June 21, 1952 in Boston. In 1953, he traveled to France for the traditional Jesuit sabbatical year known as “tertianship.” There, his worldview expanded as he met the French “worker priests.” He returned to teach at Brooklyn Prep until 1957, when he moved on to LeMoyne College , in Syracuse , New York , where he taught New Testament until 1962. There he founded “International House,” an intentional community of activist students who seek to live solidarity with the third world poor, a project that continues today.

In 1957, Berrigan published his first book of poetry, “Time Without Number.” The book won the Lamont Poetry Award and was nominated for the National Book Award. His poem “Credentials,” had first caught the attention of poet Marianne Moore who recommended his poetry to publishers and became a friend:

I would it were possible to state in so

Few words my errand in the world: quite simply

Forestalling all in quiry, the oak offers his leaves

Large handedly. And in winter his integral magnificent order

Decrees, says solemnly who he is

In the great thrusting limbs that are all finally one:

a return, a permanent river and sea.

So the rose is its own credential, a certain

Unattainable effortless form: wearing its heart

Visibly, it gives us heart too: bud, fullness and fall.

[And the Risen Bread: Selected Poems of Daniel Berrigan, 1957-1997, edited by John Dear]

After that first book, Berrigan began publishing one or two books of poetry and prose each year for the rest of his life. His early books include The Bride: Essays in the Church; Encounters; The Bow in the Clouds; The World for Wedding Ring; No One Walks Waters; They Call us Dead Men; Love, Love at the End; and False Gods, Real Men.

Denied permission to accompany his younger brother Philip, a Josephite priest, on a Freedom Ride through the South, Berrigan went to Paris on sabbatical in 1963, and then on to Czechoslovakia, Hungary and South Africa. On his return, he began to speak out against U.S. military involvement in Vietnam and co-founded the Catholic Peace Fellowship. In 1964, along with his brother Philip, A.J. Muste, Jim Forest and other peacemakers, he attended a retreat hosted by Thomas Merton at the Abbey of Gethsemani. That retreat marked a turning point for Merton and the Berrigans as the committed themselves to write and speak out against war and nuclear weapons, and advocate Christian peacemaking.

Merton recorded his meeting with Berrigan in the early 1960s in “Conjectures of a Guilty Bystand,” calling Berrigan “an altogether winning and warm intelligence and a man who, I think, has more than anyone I have ever met the true wide-ranging and simple heart of the Jesuit: zeal, compassion, understanding and uninhibited religious freedom. Just seeing him restores one’s hope in the church.”

In 1965, he marched in Selma, became assistant editor of “Jesuit Missions,” and co-founded Clergy and Laity Concerned about Vietnam with Rabbi Abraham Heschel. He began a grueling weekly speaking schedule across the country that continued until about ten years ago.

In November, 1965, a young Catholic Worker named Roger LaPorte immolated himself in front of the United Nations. After speaking at a private liturgy for LaPorte, Berrigan was ordered to leave the country immediately by his Jesuit superiors. Berrigan began a six month journey throughout Latin America. His expulsion cause a national stir throughout the media, and Berrigan returned to New York and 1967, because the first Catholic chaplain at Cornell University. His book, “Consequences: Truth and..” chronicled his journeys to Selma, South Africa and Latin America.

On October 22, 1967, Berrigan was arrested for the first time with hundreds of students protesting the war at the Pentagon. “For the first time,” he wrote in his journal in the D.C. Jail, “I put on the prison blue jeans and denim shirt; a clerical attire I highly recommend for a new church.” In February, 1968, he traveled to North Vietnam with Howard Zinn to receive three U.S. Air Force personnel who were being released. While they awaited their meeting with the VietCong, they took cover in a Hanoi shelter as U.S. bombs fell around him. His diary of his trip to North Vietnam, “Night Flight to Hanoi” was published later that year.

On May 17th, 1968, along with his brother Philip and eight others, Berrigan burned three hundred A-1 draft files in Catonsville, Maryland, in a protest against the Vietnam war. “Our apologies, good friends,” Dan wrote in the Catonsville Nine statement, “for the fracture of good order, the burning of paper instead of children, the angering of the orderlies in the front parlor of the charnel house. We could not, so help us God, do otherwise.” Their action attracted massive national and international press, and led to hundreds of similar demonstrations. After an explosive three day trial in October, he was found guilty of destruction of property.

In his autobiography, “To Dwell in Peace,” Berrigan reflected on the effect of the Catonsville protest:

The act was pitiful, a tiny flare amid the consuming fires of war. But Catonsville was like a firebreak, a small fire lit, to contain and conquer a greater. The time, the place, were weirdly right. They spoke for passion, symbol, reprisal. Catonsville seemed to light up the dark places of the heart, where courage and risk and hope were awaiting a signal, a dawn. For the remainder of our lives, the fires would burn and burn, in hearts and minds, in draft boards, in prisons and courts. A new fire, new as a Pentecost, flared up in eyes deadened and hopeless, the noble powers of soul given over to the “powers of the upper air.” “Nothing can be done!” How often we had heard that gasp: the last of the human, of soul, of freedom. Indeed, something could be done, and was. And would be.

The Catonsville Nine Protest was followed extensively around the world, in large part because of the shock of two Catholic priests facing prison for a peace protest.

In his 1969 bestseller, “No Bars to Manhood,” Berrigan wrote: “We have assumed the name of peacemakers, but we have been, by and large, unwilling to pay any significant price. And because we want the peace with half a heart and half a life and will, the war, of course, continues, because the waging of war, by its nature, is total–but the waging of peace, by our own cowardice, is partial…There is no peace because there are no peacemakers. There are no makers of peace because the making of peace is at least as costly as the making of war–at least as exigent, at least as disruptive, at least as liable to bring disgrace and prison and death in its wake.”

Back at Cornell, Berrigan wrote the best-selling play, “The Trial of the Catonsville Nine,” which later opened in New York and Los Angeles, and became a film under the direction of actor Gregory Peck. The play has been performed hundreds of times around the world, and continues to be performed as a statement against war.

“We are not allowed to be silent while preparations for mass murder proceed in our name, with our money, secretly.”When Berrigan and his co-defendants were to report to prison to begin their sentences in April 1970, both Berrigans went “underground” instead of turning themselves in. For five months, Daniel Berrigan traveled through the Northeast, speaking to the media, writing articles against the war, and occasionally appearing in public, much to the anger and frustration of J. Edgar Hoover and the F.B.I., which eventually tracked him down and arrested him on August 11, 1970, at the home of theologian William Stringfellow on Block Island, off the coast of Rhode Island. He was brought to the Danbury, Connecticut Federal Prison where he spent eighteen months. On June 9, 1971, while having his teeth examined, he suffered a massive allergic reaction to a misfired novacain injection and nearly died. On February 24, 1972, he was released.

In “The Dark Night of Resistance,” a bestseller written during his months underground, Berrigan used St. John of the Cross’ “Dark Night of the Soul” as a guide for anti-war resisters. Harvard professor Robert Coles recorded a series of conversations with Berrigan during his months in hiding in Boston, later published as “The Geography of Faith.” “America is Hard to Find” collected letters and articles from underground and prison, and was published along with “Trial Poems” and “Prison Poems.” His prison diary, “Lights on in the House of the Dead,” another bestseller, recorded his Danbury experience.

During the late 1960s and early 1970s, Berrigan attracted widespread media attention, was on the cover of “Time” magazine, and became the focus of intense national debate not only about the war, but how people of faith should oppose the war. He become one the most well known priests in the world, and consistently called for the Church to abolish its just war theory and return to the nonviolence of Jesus as recorded in the Gospel.

While he was underground, Berrigan wrote a widely-circulated open letter, first published in the “Village Voice,” to the “Weathermen,” the underground group of violent revolutionaries who blew up buildings in opposition to U.S. wars. “The death of a single human is too heavy a price to pay for the vindication of any principle, however sacred,” Berrigan wrote. Some credited his statement as a major reason for the break up of the Weather Underground.

In 1972, the U.S. filed indictments against the Berrigans and other activists charging them with threatening to kidnap Secretary of State Henry Kissinger. The trial in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, aimed mainly at Philip Berrigan was the longest trial in U.S. history, up to that time, and resulted in a mistrial and equivalent acquittal. Afterwards, Berrigan spent six months in Paris living and studying with Buddhist monk, Thich Nhat Hanh, collaborating on a book of conversations about peace, called “The Raft is not the Shore.”

In 1973, after teaching at Union Theological Seminary and Fordham University, Berrigan joined the New York West Side Jesuit Community on Manhattan’s Upper West Side, where he lived with some thirty other Jesuits for the rest of his life.

After the indictments and mistrial in Harrisburg, the Berrigans turned their attention to the U.S. nuclear weapons industry and embarked on resistance as a way of life. On September 9, 1980, with Philip and six friends, Berrigan walked in to the General Electric headquarters in King of Prussia, Pennsylvania and hammered on unarmed nuclear weapon nosecones. They were arrested, tried, convicted and faced up to ten years in prison for the felony charge of destruction of government property. Their “Plowshares” action opened a new chapter in the history of nonviolent resistance and the anti-nuclear movement. Berrigan drew inspiration from the biblical prophet Isaiah who wrote that one day, “They shall beat their swords into plowshares and their spears into pruning hooks; one nation shall not raise the sword against another, nor shall they train for war again”(Isaiah 2:4).

During their 1981 trial in Philadelphia, which was later dramatized in the film, “In the King of Prussia,” starring Martin Sheen, Berrigan said:

The only message I have to the world is: We are not allowed to kill innocent people. We are not allowed to be complicit in murder. We are not allowed to be silent while preparations for mass murder proceed in our name, with our money, secretly…It’s terrible for me to live in a time where I have nothing to say to human beings except, “Stop killing.” There are other beautiful things that I would love to be saying to people. There are other projects I could be very helpful at. And I can’t do them. I cannot. Because everything is endangered. Everything is up for grabs. Ours is a kind of primitive situation, even though we would call ourselves sophisticated. Our plight is very primitive from a Christian point of view. We are back where we started. Thou shalt not kill; we are not allowed to kill. Everything today comes down to that–everything.

Over 100 plowshares anti-nuclear demonstrations have occurred since 1980, including in England, Ireland, Germany and Australia.

As he continued to speak each week around the country and publish books of poetry and essays, Berrigan also served as a hospital chaplain in Manhattan at St. Rose’s Home for the poor, and then at St. Vincent’s Hospital, with cancer patients and later with AIDS patients, which he chronicled in his books, “We Die before we live,” and “Sorrow Built a Bridge.” In 1984, he traveled to El Salvador and Nicaragua to learn first hand from church leaders about the effects of the U.S. wars there, and wrote about the journey in “Steadfastness of the Saints.”

In 1985, filmmaker Roland Joffe invited Berrigan to Paraguay, Argentina and Colombia to serve as advisor to the film, “The Mission.” He also had a small part, alongside Robert DeNiro, Jeremy Irons and Liam Neeson. Berrigan published an account about the making of the film, the Jesuit missions in Latin America of 1770s, and their relevance to contemporary efforts against war today, in his book, “The Mission.” In 1988, he published his autobiography, “To Dwell In Peace.”

In the mid-1980s, Berrigan began to publish a series of twenty scripture commentaries on the books of the Hebrew Bible. And the Risen Bread: Selected Poems of Daniel Berrigan, 1957-1997, edited by John Dear, was published in 1996.

Dan was my greatest friend and teacher, for over thirty five years. We traveled the nation and the world together; went to jail together; and I edited five books of his writings. But all along I consider him one of the most important religious figures of the last century, right alongside with Gandhi, Martin Luther King, Jr., Thomas Merton, Dorothy Day and his brother Philip. Dan and Phil inspired millions of people around the world to speak out against war and work for peace, and helped turn the Catholic church back to its Gospel roots of peace and nonviolence. I consider him not just a legendary peace activist but one of the greatest saints and prophets of modern times. I will write more about him, but for now, I celebrate his extraordinary life, and invite everyone to ponder his great witness.

Thank you, Dan. May we all take heart from your astonishing peacemaking life, and carry on the work to abolish war, poverty and nuclear weapons.

xxx

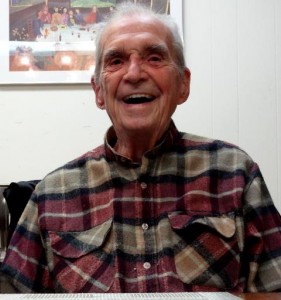

Dan Berrigan protesting the rededication of the Intrepid war museum aircraft carrier on the west side of Manhattan, Nov. 2008. Photo: Ed Hedemann

from the Washington Post

Daniel J. Berrigan, pacifist priest who led antiwar protests, dies at 94

The life of pacifist priest, the Rev. Daniel Berrigan

by Colman McCarthy

The Rev. Daniel J. Berrigan, a writer, teacher and longtime peace activist whose repeated acts of civil disobedience put him at odds with his government and the Roman Catholic Church but made him a major figure in the radical left of the 1960s and 1970s, died April 30 at a Jesuit residence at Fordham University in the Bronx. He was 94.

The cause was a cardiovascular ailment, said the Rev. James Yannarell, a priest affiliated with the Fordham Jesuit community.

In May 1968, Father Berrigan, his brother and fellow priest Philip Berrigan, and seven other activists entered a Selective Service office in Catonsville, Md.

They gathered hundreds of draft files, lugged them outside and, with a recipe of kerosene and soap chips taken from a Green Berets handbook, burned them to ashes. The Catonsville Nine, as they became known, were arrested, and in a five-day trial in October 1968, they were found guilty of destruction of government property.

Father Berrigan wrote a play about the event, “The Trial of the Catonsville Nine.”

“Our apologies, good friends,” he wrote, “for the fracture of good order, the burning of paper instead of children, the angering of the orderlies in the front of the charnel house. We could not, so help us God, do otherwise.”

The judge sentenced Father Berrigan, then 47, to three years in federal prison. Philip Berrigan, who had been charged in earlier protests, received a longer sentence.

In 1970, after the appeals ran out, Father Berrigan refused orders to report to federal prison in Danbury, Conn. He went underground, on the lam from safe house to safe house, and

spent four months dodging an FBI manhunt. After many false leads, he was caught on Block Island, off the coast of Rhode Island. Days before he was captured, he spoke at a church in in Philadelphia’s Germantown neighborhood, saying, “We have chosen to be branded peace criminals by war criminals.”

He ultimately served two years in prison.

Father Berrigan was a willing recidivist who was first arrested in 1967. His rap sheet would eventually be filled with arrests and convictions from protests at weapons laboratories and at the Pentagon.

Daniel Joseph Kerrigan was born May 9, 1921, in Virginia, Minn., the fifth of six sons of a pro-union father a mother who opened her home to the poor.

In 1939, Daniel Berrigan entered the former St. Andrew-on-the-Hudson Jesuit novitiate near Poughkeepsie, N.Y.

During his years of theological training, he wrote poetry and taught at Catholic high schools, preparing for a career of teaching or pastoring. He was ordained in 1952.

In the mid-1950s, he taught at Brooklyn Preparatory High School in New York. From 1957 to 1962, he taught theology at Le Moyne College in Syracuse, N.Y.

Over the decades, Father Berrigan’s forays into the academy also included stints at Cornell University, the University of Detroit, Loyola University New Orleans, DePaul University and the University of California at Berkeley. During the Vietnam War years and after, he believed that universities had become tools of the government, military and corporate giants.

With no conventional ministry, Father Berrigan operated for more than 40 years out of a small commune known as the West Side Jesuit Community on West 98th Street in Manhattan. He aligned himself with Dorothy Day and the pacifist Catholic Worker movement and formed a friendship with Thomas Merton, the Trappist monk who was also moving away from conventional priestly piety by condemning U.S. involvement in Vietnam.

In 1968, Father Berrigan traveled with Howard Zinn, the liberal political activist and historian, to North Vietnam in a successful effort to bring back three captured U.S. pilots. Father Berrigan was affiliated with several Catholic antiwar groups and later ministered to AIDS patients.

In 1980, he and his brother Philip were instrumental in forming the Plowshares Movement, a loose coalition of pacifists who were often arrested for acts of civil disobedience at military bases and other sites, including a nuclear-missile facility in Pennsylvania.

Among those jailed was actor Martin Sheen, who once said, “Mother Teresa drove me back to Catholicism, but Daniel Berrigan keeps me there.

In 1965, Cardinal Francis Spellman, a supporter of the Vietnam War, told Father Berrigan’s Jesuit superiors to get the agitator out of New York City. He was sent to South America, but seeing the conditions in the slums of Peru and Brazil made him more militant, not less. He believed that the Catholic Church too often sided with the rich, and he criticized a U.S. foreign policy that included the sale of weapons to rightist military regimes.

Father Berrigan took aim at his fellow Jesuits when he wrote his “Ten Commandments for the Long Haul” (1981).

“The Jesuits are masters of invention,” he wrote in his provocative manifesto. “They come out of the culture, they know how to take its pulse, try its winds and trim their sails. Nothing extravagant, nothing ahead of its time, nothing too fast. Consensus! Consensus!”

Father Berrigan wrote more than 40 books, including a 1987 autobiography, “To Dwell in Peace.” He wrote numerous volumes of poetry, including “Time Without Number” (1957), which won the Lamont Poetry Award, and “Prison Poems” (1973).

His brother Philip died in 2002. Survivors include a sister.

In a 2008 interview in the Nation magazine, Father Berrigan echoed a line of Mother Teresa’s that spiritual people should be more concerned about being faithful than being successful.

“The good is to be done because it is good, not because it goes somewhere,” he said. “I believe if it is done in that spirit it will go somewhere, but I don’t know where. . . . I have never been seriously interested in the outcome. I was interested in trying to do it humanely and carefully and nonviolently and let it go.”

Colman McCarthy is a former Washington Post columnist.

xxx

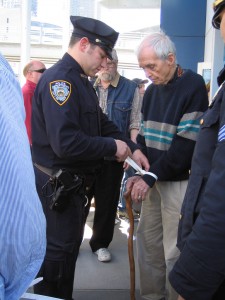

Elmer Maas and Dan Berrigan during a peace vigil in New York’s Union Square immediately after the Sept. 11, 2001, attacks. Photo: Ed Hedemann

from the New York Times

Daniel J. Berrigan, Defiant Priest Who Preached Pacifism, Dies at 94

by Daniel Lewis

The Rev. Daniel J. Berrigan, a Jesuit priest and poet whose defiant protests helped shape the tactics of opposition to the Vietnam War and landed him in prison, died on Saturday in New York City. He was 94.

His death was confirmed by the Rev. James Martin, a Jesuit priest and editor at large at America magazine, a national Catholic magazine published by Jesuits. Father Berrigan died at Murray-Weigel Hall, the Jesuit infirmary at Fordham University in the Bronx.

The United States was tearing itself apart over civil rights and the war in Southeast Asia when Father Berrigan emerged in the 1960s as an intellectual star of the Roman Catholic “new left,” articulating a view that racism and poverty, militarism and capitalist greed were interconnected pieces of the same big problem: an unjust society.

It was an essentially religious position, based on a stringent reading of the Scriptures that some called pure and others radical. But it would have explosive political consequences as Father Berrigan; his brother Philip, a Josephite priest; and their allies took their case to the streets with rising disregard for the law or their personal fortunes.

A defining point was the burning of Selective Service draft records in Catonsville, Md., and the subsequent trial of the so-called Catonsville Nine, a sequence of events that inspired an escalation of protests across the country; there were marches, sit-ins, the public burning of draft cards and other acts of civil disobedience.

The catalyzing episode occurred on May 17, 1968, six weeks after the murder of the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and the outbreak of new riots in dozens of cities. Nine Catholic activists, led by Daniel and Philip Berrigan, entered a Knights of Columbus building in Catonsville and went up to the second floor, where the local draft board had offices. In front of astonished clerks, they seized hundreds of draft records, carried them down to the parking lot and set them on fire with homemade napalm.

Some reporters had been told of the raid in advance. They were given a statement that said in part, “We destroy these draft records not only because they exploit our young men but because they represent misplaced power concentrated in the ruling class of America.” It added, “We confront the Catholic Church, other Christian bodies and the synagogues of America with their silence and cowardice in the face of our country’s crimes.”

In a year sick with images of destruction, from the Tet offensive in Vietnam to the murder of Dr. King, a scene was recorded that had been contrived to shock people to attention, and did so. When the police came, the trespassers were praying in the parking lot, led by two middle-aged men in clerical collars: the big, craggy Philip, a decorated hero of World War II, and the ascetic Daniel, waiting peacefully to be led into the van.

Protests and Arrests

In the years to come, well into his 80s, Daniel Berrigan was arrested time and again, for greater or lesser offenses: in 1980, for taking part in the Plowshares raid on a General Electric missile plant in King of Prussia, Pa., where the Berrigan brothers and others rained hammer blows on missile warheads; in 2006, for blocking the entrance to the Intrepid naval museum in Manhattan.

“The day after I’m embalmed,” he said in 2001, on his 80th birthday, “that’s when I’ll give it up.”

It was not for lack of other things to do. In his long career of writing and teaching at Fordham and other universities, Father Berrigan published a torrent of essays and broadsides and, on average, a book a year, almost to the time of his death.

Among the more than 50 books were 15 volumes of poetry — the first of which, “Time Without Number,” won the prestigious Lamont Poetry Prize, given by the Academy of American Poets, in 1957 — as well as autobiography, social criticism, commentaries on the Old Testament prophets and indictments of the established order, both secular and ecclesiastic.

While he was known for his wry wit, there was a darkness in much of what Father Berrigan wrote and said, the burden of which was that one had to keep trying to do the right thing regardless of the near certainty that it would make no difference. In the withering of the pacifist movement and the country’s general support for the fighting in Iraq and Afghanistan, he saw proof that it was folly to expect lasting results.

“This is the worst time of my long life,” he said in an interview with The Nation in 2008. “I have never had such meager expectations of the system.”

What made it bearable, he wrote elsewhere, was a disciplined, implicitly difficult belief in God as the key to sanity and survival.

Many books by and about Father Berrigan remain in print, and a collection of his work over half a century, “Daniel Berrigan: Essential Writings,” was published in 2009.

He also had a way of popping up in the wider culture: as the “radical priest” in Paul Simon’s song “Me and Julio Down by the Schoolyard”; as inspiration for the character Father Corrigan in Colum McCann’s 2009 novel, “Let the Great World Spin.” He even had a small movie role, appearing as a Jesuit priest in “The Mission” in 1989.

But his place in the public imagination was pretty much fixed at the time of the Catonsville raid, as the impish-looking half of the Berrigan brothers — traitors and anarchists in the minds of a great many Americans, exemplars to those who formed what some called the ultra-resistance.

After a trial that served as a platform for their antiwar message, the Berrigans were convicted of destroying government property and sentenced to three years each in the federal prison in Danbury, Conn. Having exhausted their appeals, they were to begin serving their terms on April 10, 1970.

Instead, they raised the stakes by going underground. The men who had been on the cover of Time were now on the Federal Bureau of Investigation’s most-wanted list. As Daniel explained in a letter to the French magazine Africasia, he was not buying the “mythology” fostered by American liberals that there was a “moral necessity of joining illegal action to legal consequences.” In any case, both brothers were tracked down and sent to prison.

Philip Berrigan had been the main force behind Catonsville, but it was mostly Daniel who mined the incident and its aftermath for literary meaning — a process already underway when the F.B.I. caught up with him on Block Island, off the Rhode Island coast, on Aug. 11, 1970. There was “The Trial of the Catonsville Nine,” a one-act play in free verse drawn directly from the court transcripts, and “Prison Poems,” written during his incarceration in Danbury.

In “My Father,” he wrote:

I sit here in the prison ward

nervously dickering with my ulcer

a half-tamed animal

raising hell in its living space

But in 500 lines the poem talks as well about the politics of resistance, memories of childhood terror and, most of all, the overbearing weight of his dead father:

I wonder if I ever loved him

if he ever loved us

if he ever loved me.

The father was Thomas William Berrigan, a man full of words and grievances who got by as a railroad engineer, labor union officer and farmer. He married Frida Fromhart and had six sons with her. Daniel, the fourth, was born on May 9, 1921, in Virginia, Minn.

When he was a young boy, the family moved to a farm near Syracuse to be close to his father’s family.

In his autobiography, “To Dwell in Peace,” Daniel Berrigan described his father as “an incendiary without a cause,” a subscriber to Catholic liberal periodicals and the frustrated writer of poems of no distinction.

“Early on,” he wrote, “we grew inured, as the price of survival, to violence as a norm of existence. I remember, my eyes open to the lives of neighbors, my astonishment at seeing that wives and husbands were not natural enemies.”

Battles With the Church

Born with weak ankles, Daniel could not walk until he was 4. His frailty spared him the heavy lifting demanded of his brothers; instead he helped his mother around the house. Thus he seemed to absorb not only his father’s sense of life’s unfairness but also an intimate knowledge of how a man’s rage can play out in the victimization of women.

At an early age, he wrote, he believed that the church condoned his father’s treatment of his mother. Yet he wanted to be a priest. After high school he earned a bachelor’s degree in 1946 from St. Andrew-on-Hudson, a Jesuit seminary in Hyde Park, N.Y., and a master’s from Woodstock College in Baltimore in 1952. He was ordained that year.

Sent for a year of study and ministerial work in France, he met some worker-priests who gave him “a practical vision of the Church as she should be,” he wrote. Afterward he spent three years at the Jesuits’ Brooklyn Preparatory School, teaching theology and French, while absorbing the poetry of Robert Frost, E. E. Cummings and the 19th-century Jesuit Gerard Manley Hopkins. His own early work often combined elements of nature with religious symbols.

But he was not to become a pastoral poet or live the retiring life he had imagined. His ideas were simply turning too hot, sometimes even for friends and mentors like Dorothy Day, the co-founder of the Catholic Worker Movement, and the Trappist intellectual Thomas Merton.

At Le Moyne College in Syracuse, where he was a popular professor of New Testament studies from 1957 to 1963, Father Berrigan formed friendships with his students that other faculty members disapproved of, inculcating in them his ideas about pacifism and civil rights. (One student, David Miller, became the first draft-card burner to be convicted under a 1965 law.)

Father Berrigan was effectively exiled in 1965, after angering the hawkish Cardinal Francis Spellman in New York. Besides Father Berrigan’s work in organizing antiwar groups like the interdenominational Clergy and Laymen Concerned About Vietnam, there was the matter of the death of Roger La Porte, a young man with whom Father Berrigan said he was slightly acquainted. To protest American involvement in Southeast Asia, Mr. La Porte set himself on fire outside the United Nations building in November 1965.

Soon, according to Father Berrigan, “the most atrocious rumors were linking his death to his friendship with me.” He spoke at a service for Mr. La Porte, and soon thereafter the Jesuits, widely believed to have been pressured by Cardinal Spellman, sent him on a “fact-finding” mission among poor workers in South America. An outcry from Catholic liberals brought him back after only three months, enough time for him to have been radicalized even further by the facts he had found.

For the Jesuits, Father Berrigan was both a magnet to bright young seminarians and a troublemaker who could not be kept in any one faculty job too long.

At onetime or another he held faculty positions or ran programs at Union Seminary, Loyola University New Orleans, Columbia, Cornell and Yale. Eventually he settled into a long tenure at Fordham, the Jesuit university in the Bronx, where for a time he had the title of poet in residence.

Father Berrigan was released from the Danbury penitentiary in 1972; the Jesuits, alarmed at his failing health, managed to get him out early. He then resumed his travels.

After visiting the Middle East, he bluntly accused Israel of “militarism” and the “domestic repressions” of Palestinians. His remarks angered many American Jews. “Let us call this by its right name,” wrote Rabbi Arthur Hertzberg, himself a contentious figure among religious scholars: “old-fashioned theological anti-Semitism.”

Nor was Father Berrigan universally admired by Catholics. Many faulted him for not singling out repressive Communist states in his diatribes against the world order, and later for not lending his voice to the outcry over sexual abuse by priests. There was also a sense that his notoriety was a distraction from the religious work that needed to be done.

Not the least of his long-running battles was with the church hierarchy. He was scathing about the shift to conservatism under Pope John Paul II and the “company men” he appointed to high positions.

Much of Father Berrigan’s later work was concentrated on helping AIDS patients in New York City. In 2012, he appeared in Zuccotti Park in Lower Manhattan to support the Occupy Wall Street protest.

He also devoted himself to writing biblical studies. He felt a special affinity for the Hebrew prophets, especially Jeremiah, who was chosen by God to warn of impending disaster and commanded to keep at it, even though no one would listen for 40 years.

A brother, Jerry, died in July at age 95, and another brother, Philip, died in 2002 at age 79.

Father Berrigan seemed to reach a poet’s awareness of his place in the scheme of things, and that of his brother Philip, who left the priesthood for a married life of service to the poor and spent a total of 11 years in prison for disturbing the peace in one way or another before his death from cancer in 2002. While they both still lived, Daniel Berrigan wrote:

My brother and I stand like the fences

of abandoned farms, changed times

too loosely webbed against

deicide homicide

A really powerful blow

would bring us down like scarecrows.

Nature, knowing this, finding us mildly useful

indulging also

her backhanded love of freakishness

allows us to stand.

Christopher Mele contributed reporting.

xxx