Gordon Maham, 96-years-old and a long-time anti-nuclear activist, died on July 9 at his farm in Ohio. Gordon helped build the Y-12 plant in Oak Ridge, Tennessee, and quit the Manhattan Project when he heard about Hiroshima and his role in building the bomb. He then lost his war industry draft exemption and served three years in federal prison as a post-war conscientious objector. His life’s journey continues to inspire.

Read more about Gordon’s life…

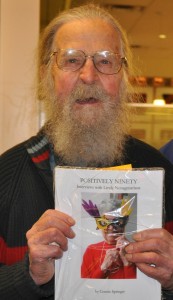

The following, written by Connie Springer, is from her book POSITIVELY NINETY: Interviews with Lively Nonagenarians. The book sells for $25 + shipping, and can be ordered from http://conniespringer.com or by emailing larkspur@fuse.net

Gordon Maham: A Peaceful Planet Person

At 91, Gordon Maham spends just about every waking moment working for causes that are dear to him. “I’ve fought a lot of battles,” he says, “and I’ve walked across plenty of lines to end wars and stop bombs.”

His stance against violence landed him three years in the Ashland, Kentucky Federal Penitentiary during World War II for not registering for the draft. He has spent the ensuing decades spreading his creed of peace and helping others. “Gordon is one of the kindest, gentlest people I have ever known,” says a friend.

On my first visit to Gordon’s house the weather is blustery, and using the ax he has had since childhood he splits wood for the fireplace. A month later when I arrive, spring is in the air as Gordon tours me around his property. Prominent in his backyard are a picnic table from which deer eat and a barn that houses his elderly, blind horse and stray cats which he feeds. His friends say that Gordon treats animals, insects, and buzzards with as much love and respect as he shows people.

On January 3, 1917 the doctor arrived by horse and buggy to deliver Gordon at home in rural Cincinnati, north of the present day Tri-County area. Gordon joined a family of Irish-Dutch tenant farmer parents and a two-year old brother, Lawrence. Although his dad later succeeded in purchasing his own farm near Kemper and Winton Roads, Gordon remembers the family as struggling. Until he went off to college, the family didn’t own a phone.

Gordon guesses he got his tendency toward helping others more than taking care of his own needs from his mother. “My mom never knew the word ‘can’t’ when someone needed help,” he observes.

His parents taught Gordon to grow and can his own foods, be self-sustaining, and eat a healthy diet. During Prohibition his father made homebrew and brought it to neighborhood parties, though Gordon remembers his dad insisting on everything in moderation.

Gordon’s anti-war beliefs were kindled by a family ethic of non-violence. He rarely saw his parents angry and was encouraged not to fight with his brother. As a child Gordon attended Pleasant Run Presbyterian Church and at ten was baptized on his farm. In biblical studies he was especially impressed with the part about “thou shalt not kill.” He figures he’s been a pacifist since grade school.

In his early years he and forty other kids attended a one-room schoolhouse. It was the time of the Great Depression, and with an entrepreneurial spirit, from fifth to eighth grades he worked for $8 a month as a school janitor, building fires in a big stove, cutting grass, and sweeping the floor. By the age of ten he was a skilled hunter, trapper, and skinner of animals, selling his prey to customers to earn extra money to help his parents pay the mortgage. He still remembers the bounty that each animal brought: a possum fetched $2, a star skunk $5, a raccoon, $8, and a fox, $10.

Later Gordon entered Hamilton High School, a considerable distance from his house. He would ride his bike two miles, catch a bus, and then walk a mile from the bus station to school. He had lots of fun in school, and his excellent grades earned him recognition in the National Honor Society. He continued to help support the family by stacking bales of hay and cutting corn stalks for ten cents an hour.

Had it not been for the suggestion of his dad’s friend during a card game, he would never have thought of going to college. Gordon decided to channel his enthusiasm for drafting and construction work into studying civil engineering at the University of Cincinnati, all the while working at night for Freckling Dairy. While a student he lived at Mrs. Krakoff’s boarding house in Clifton with nine other boys, enjoying one square meal a day.

Gordon never obtained financial aid; instead he worked his way through college juggling three jobs: raking leaves and doing other maintenance work for the National Youth Administration, selling hats for the downtown Thurman Company, and transporting corpses from the hospital to the doctor for autopsies.

After graduating from the University of Cincinnati in 1941 with a civil engineering degree, Gordon was hired to work with the Army Corps of Engineers in Panama designing Diablo Heights, a project to construct a third set of locks capable of carrying larger vessels than was possible with the existing locks. “That was a good life,” he says of the year he spent there, learning Spanish and sowing his oats. When he heard rumors that they were going to “send the draft dodgers back and put them in the army,” Gordon quit and moved to Brazil.

In the northern coastal city of Belem, Brazil, he worked building Navy quarters and constructing bases for landplanes and World War II PBY (Patrol Bomber Consolidated Aircraft) seaplanes. He dabbled in Portuguese and learned the dangers of the Brazilian jungles, witnessing a colleague being fatally bitten by a boa constrictor.

Told that he could beat the draft board by taking a job with the Tennessee Valley Authority in Knoxville, Tennessee, Gordon eagerly accepted. “I didn’t know I was going to be making nuclear bombs,” he winces.

Reporting for work, he was clueless that his job was to help build the ultra-secret Y-12 National Security Complex plant. Y-12 had been established to enrich uranium as part of the Manhattan Project, leading to the creation of the first atomic bomb. He was later horrified to learn that Y-12 produced some of the uranium-235 for Little Boy, the nuclear weapon obliterating Hiroshima, Japan on August 6, 1945. After three years Gordon realized the impact of what he was doing and immediately quit.

During this time he became engaged to his boss’ daughter, Doris, but succumbing to his early belief that there were no such words as “have to,” he canceled the wedding.

When he didn’t report for his military induction, he was arrested and sentenced to three years in the federal penitentiary near Ashland, Kentucky. Surprisingly he is not bitter about the time spent in prison. “I had three good years there,” he comments. “It was a nice experience.” He asked for “no parole, no probation” but did receive credit for good behavior.

While incarcerated, Gordon busied himself with desegregating the prison, playing the piano, reading books on every topic from spherical trigonometry to musician biographies, and teaching drafting classes to the inmates. Supplied with a drafting table, he earned $25 by drawing up plans for a cigar factory being built in Ashland and by laying out a subdivision for the guards.

He found the medical care in jail abysmal. “I never trusted the doctor or the dentist in the penitentiary,” he says. “When I felt dizzy and pressed the button for help, it was two hours until somebody came.”

Gordon didn’t want his parents to see him in prison but did receive visits from Doris, his former fiancée, and her mother.

He had always had friends and family who were Jehovah’s Witnesses (a religion that teaches not to kill and a faith that both his brother and one of his sons took up). When he was released from prison, his Jehovah’s Witness friends helped him find contract work in Pittsburgh doing drafting of industrial buildings. Later he was hired by George Richardson Engineers to work on highway systems.

In Pittsburgh he was introduced to his future wife, Mary Wasnik, of Ukrainian background and from a family of peaceful Jehovah’s Witnesses. After marrying in 1952, Gordon and Mary lived with her folks in Pittsburgh. “They basically adopted me. I’m not too hard to get along with,” he adds, “as long as violence isn’t introduced.” The next year Mary gave birth to their first child, Allen, followed by Bob, Tom, and Marilyn.

In time, Gordon learned that his father, still in Hamilton, Ohio, had suffered a stroke and heart attack. Gordon bought a trailer and left for Cincinnati. Finding him not well, he decided to move his family back to Ohio, buying a cottage in College Hill. Soon dismayed by rowdy neighbors (son Allen was hit on the head with a revolver by one ruffian), the family moved further into the country to his present Northgate location.

Gordon says his children were raised “betwixt and between,” taking the good things about religion and leaving out what wasn’t useful. His first two children he brought to church every Sunday; Marilyn he took to the park instead.

“I’d play with them, swing them in a circle,” he recalls. “I gave them the chance to do a lot of things that a strict parent wouldn’t have.” Never one to be bossy, Gordon reared his kids by letting them learn on their own. He was also a friend and helpmate to other kids in the neighborhood.

At 59 Gordon quit civil engineering work to take care of his ailing mother. “That was the same year I quit paying taxes,” he muses.

After his mother died, Gordon started attending the West End’s Community Church of Cincinnati led by pacifist and social activist Reverend Maurice McCracken. “Mac” and the church members shared Gordon’s values in favor of prison reform, opposing nuclear power and weapons, and supporting the hungry and homeless. When Gordon turned 90 last year, friends, admirers, and family members celebrated the occasion in the West End church.

Twenty years ago Gordon joined a neighborhood class action lawsuit against the nuclear-producing facility Fernald, which was accused of polluting and producing toxic waste. Receiving a small part of the settlement, every two years he must file a report of his health, which fortunately is in good shape.

He lost his only brother, Lawrence, when the latter drowned at 75. A decade later, in his mid-eighties, he lost his 81-year old wife, Mary, who as a Jehovah’s Witness refused surgery for heart problems because of her conviction against blood transfusions.

For ten years, Gordon has shared his home with his oldest son, Allen, who moved back to Cincinnati from California. Gordon’s daughter Marilyn and her husband live a mile away and are in frequent contact. His children help defray his expenses, including car insurance, tires, gas, long-distance calls, and food. Gordon, who is a vegetarian, supplements his diet with chickweed and dandelions and isn’t averse to visiting soup kitchens.

He has lost track of how many times he’s been arrested in peaceful protests. A few times his children have joined him in demonstrations, most notably when Marilyn, Tom, and his 10-year old granddaughter accompanied him to the 1982 protest against nuclear bombs in New York’s Central Park, joining a million others. He says his kids have asked him to stop getting arrested, and when he turned 90 he agreed to their request.

But protesting is in his blood, and in April he participated in Oak Ridge’s Action for Peace protest organized by OREPA (the Oak Ridge Environmental Peace Alliance).

Gordon spends his small monthly social security check “the way I want to spend it, and that’s helping people, resisting violence, and assisting peace.” His helpfulness extends to supporting a friend dying of cancer; gathering food from food pantries to distribute to Mexican workers split up from their families; building a vegetable garden to help a friend with health problems; coming to the aid of someone getting out of jail; visiting shut-ins in nursing homes and hospitals; taking people to the doctor; and loaning money to anyone down on his/her luck. Although he can become emotionally drained from his good deeds, he relishes the challenges he faces because they are for good causes. “If I don’t have a challenge,” he assures, “I’ll make one!”

According to a friend, Gordon “calls at the opportune moment to step in, as if from God,” a phenomenon Gordon calls serendipity or “psychic.”

Taking a lot of young friends under his wing, Gordon wants to lead a new generation in the direction of compassion, dedication to good causes, and simple living. Like Thoreau, he encourages people to “simplify.”

Gordon is variously labeled as an organic farmer, a collector of junk which he rebuilds and recycles, an animal lover and protector, an environmentalist, a widower, a father of four, and a grandfather of two. But another role might be looming in his future.

Ruing how he treated his old love, Doris, sixty years ago by calling off the engagement, he proffers a ring which he has been saving for her. “I’ve always been taught to do it well or not at all,” he says.

After April’s peace protest in Oak Ridge, he walked two miles to reach Doris’ house and waited patiently for her to answer the door. Although he hasn’t yet popped the question, with any luck reconnecting with Doris will be Gordon’s next serendipity.

xxx

An obituary can be read at http://news.cincinnati.com/article/20130714/NEWS/307140027/-Last-great-radicals-dies-peacefully?gcheck=1

You can read OREPA coordinator Ralph Hutchison’s stories and memories of Gordon at http://orepa.org/gordon-maham/ – nice photos there, too!