(From the Nuclear Resister #157, June 1, 2010)

How Can I Cope?

Many people who write me – friends and supporters – ask about harsh treatment and brutality. I do not deny that in many prisons and jails these conditions do exist. One can even raise the charge of torture. In regards to myself I have not experienced such conditions. Hardships, yes, but not brutality or violence.

The hardships begin with the loss of freedom. I remember during my first incarceration, after having made pastoral visits in jail to prisoners, it was a shock as I realized the cell doors were closed and locked on me.

Jails are usually cold – or too hot – mats are hard, and not always present (as in the District of Columbia Central Cellblock), food is sometimes scarce and tasteless, clothes are inadequate (no coats or even underwear), they don’t fit, are not clean. Medical care may be hard to access, and not adequate, especially with serious needs. TVs are loud and almost always on. The noise can be horrific, even through the night. Then there is the isolation from family and friends. Phone calls are difficult and expensive. Visiting is restricted, mostly through glass, and more and more over in-house video systems.

People ask, “How do you cope?”

Especially since most of my time in recent years has been for protesting torture, experienced by those subject to School of the Americas graduates, Guantanamo Bay, Abu Ghraib, and Bagram, the U.S.-run prison in Afghanistan that is replacing Gitmo for its brutality. If this dulls the imagination there are the continuing renditions to countries that practice even more blatant torture. This goes on throughout the world.

If I start to feel sorry for myself I think of the suffering experienced in these and other horrific situations from slavery to executions. How can I really complain? Yes, it may well be called for to file complaints or act to have rules, regulations, and practices changed as has happened at Guantanamo Bay and by prison reform groups which expose such practices. Personally I question the whole prison system. As labor leader Eugene Debs said, “So long as there is a soul in prison, I am not free.” But when I think about these situations (often at night in bed), I am able to cope with my own deprivations.

Even more significant for me is to use these experiences and reflections to create empathy with all of those who suffer these horrific experiences. We are all part of this created world. Each person is sister and brother to me. Their suffering is my sorrow as well.

The gift of compassion emerges as I contemplate such misery of the human body. My situation is a gateway into the compassionate energy that fills all creation and opens me to transforming experiences that I hope to share with the world community.

For this I am grateful and value this precious time.

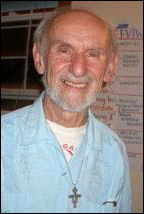

[Franciscan Friar Louis Vitale is serving a six month sentence for trespass at Fort Benning, Georgia, home of the Western Hemisphere Institute for Security and Cooperation, formerly and notoriously known as the School of the Americas. The essay, reprinted from the website of Pace e Bene, was written from the U.S. Penitentiary in Atlanta, before Vitale was moved to the federal prison at Lompoc, California, where he will complete his sentence in late July.]